Hello friends

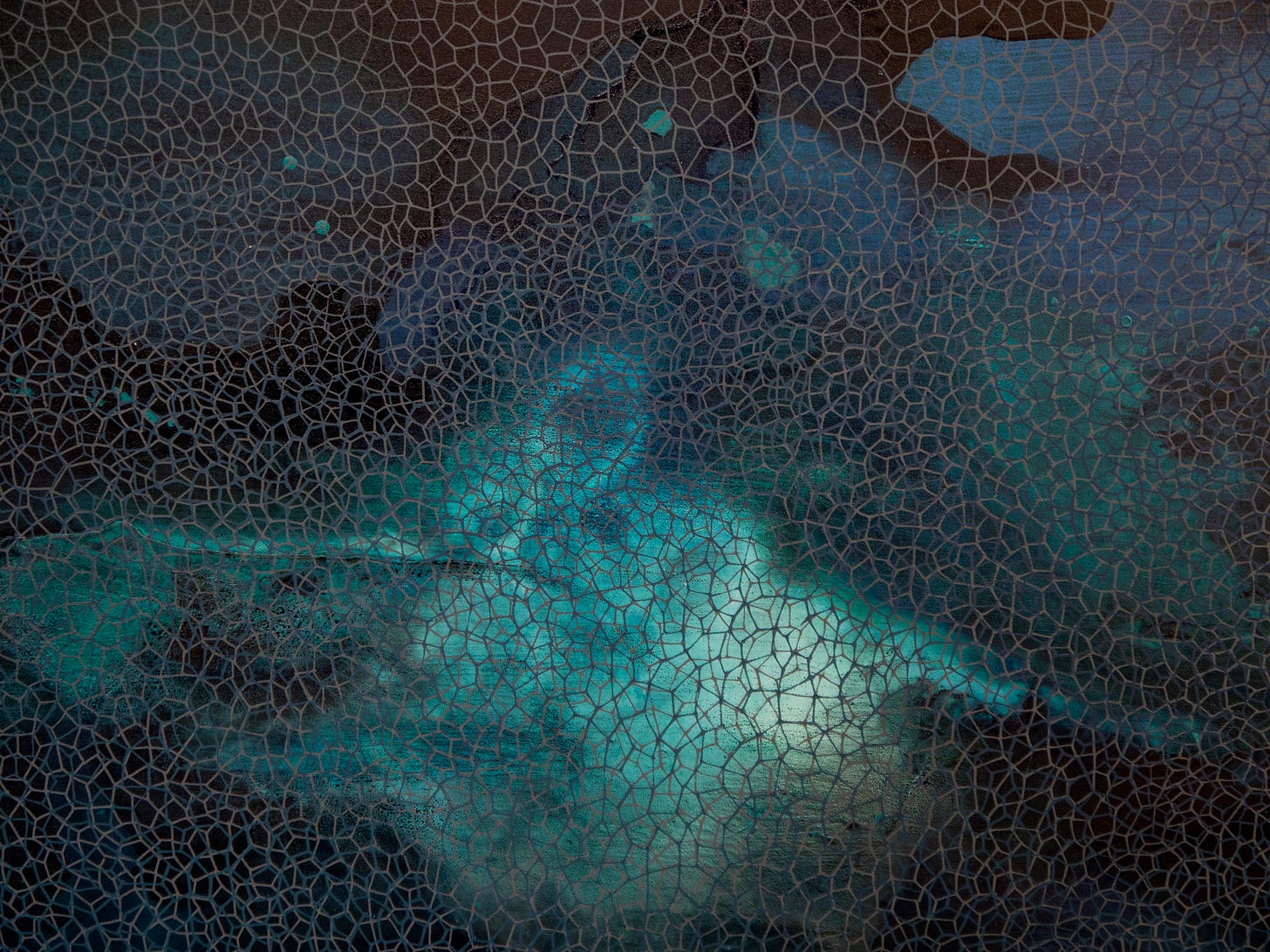

I’ve been immersed in deep, dark blue this week, working on the last big piece I’m readying for an exhibition in January.

I think I’m about halfway through this painting now. Titles drift in and out of focus as I work on it: ‘Clouded Moon, Reflected’. Or maybe just ‘Dark Water.’

It’s certainly the season of dark water here in Orkney. Last night it took the form of wind-driven rain, as Storm Ashley boomed and rumbled against our west-facing walls in the 2 am dark. A couple of nights ago the dark water of the loch was dancing under a huge full moon, its sheen like silk.

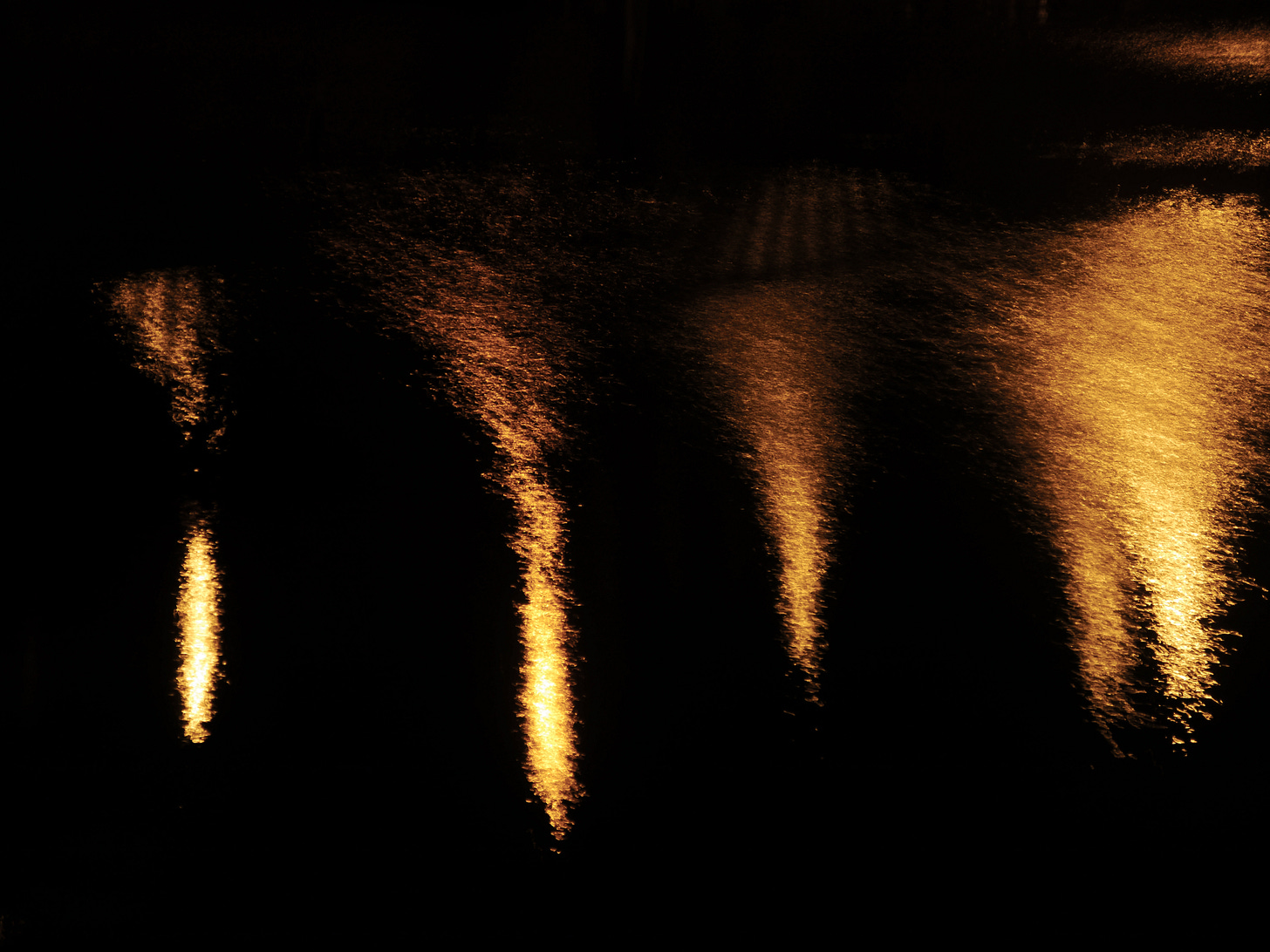

On Saturday evening, the dark water was glossy and black like oil, pooled with streetlights, as it lapped gently around the boats in Stromness harbour in the calm before last night’s storm. My partner received an aurora alert on his phone as we made our way home, but thick cloud kept the sky as black as the water.

The season of dark in the north is long. This gives us time to adjust, accept, and learn that darkness reveals what the brightness of daylight conceals.

This week I’m sharing an excerpt from my book The Clearing, from the chapter Aurora Borealis. It was written while I was spending the winter months in a small town in the north of mainland Scotland, coming to terms with the death of my parents, and thinking a lot about what the dark can teach us:

Aurora Borealis

My life here revolves around dawns, dusks, and the dark of the nights. I plot the times of these carefully as they change from day to day. Winter days are very short at this latitude, summer ones very long, and so the transition between seasons is dramatic.

Midwinter dusk comes early, darkening not long after three o’clock. I pause in whatever I am doing to watch the light drain out of the ground, soak away into the heavy sky, and sink down over the hill behind the town. I wipe a patch in the misted window to watch the glimmering river fade into the darkness. Or I put on my coat and boots to go for a walk as the afternoon smudges into grey and a thin snow goes dithering down into the water.

After dark has properly fallen, I take long, meandering walks around the little town with my camera. I take pictures of the streetlights shining onto the silent, black river, of bare trees made strange by the jaundiced glow of sodium light, of snowflakes drifting through the bright orbit of a streetlamp, of scrubby grass lit by my torch beam, and my own puffs of breath hovering briefly like ghosts on the cold air. I film the harbour lights shimmering on the sea, and the bright beads of car headlights sliding along the main A9 road that hugs the coast.

I go down to the riverbank and film the bright face of the town clock like a reflected moon in the water’s glossy, swirling surface, two kinds of time, each flowing into the other. I’m not sure what I’m looking for yet. I hope I’ll know it when I find it. But to do this work I know you have to feel your way forwards tentatively, blindfolded and fumbling.

I decide that, while I am here, I am going to wean myself off city streetlights and become comfortable with walking in the dark. Proper dark. The deep dark of the North in winter. It seems important, as if moving through the dark outside I might learn how to move through inner darkness and uncertainty with more ease.

So tonight, after nightfall, I walk to the end of the bright tunnel of streetlights to the edge of the village. But I pause under the last light, surprised to feel the unmistakeable and familiar slither of fear come to join me. A city girl, instinctively I glance behind me, scanning the silent village street, a fist of keys in my pocket - old habits die hard. It’s well past midnight now, and there are no lights on in the houses. Everyone’s asleep. I let go of my keys. I can slip away into the night unseen.

From here the footpath vanishes into an enveloping dark. I step out into it, wary, my head swivelling like an owl’s, blinking uselessly. I hold my breath to listen. I’m alert and on edge, senses all peeled back. Perhaps it’s the transition from streetlight to darkness that feels so ungrounding, that first moment of stepping out and not seeing where your foot will land.

There is no moon. It’s unusually still, but there is just enough wind moving over the hills that I can hear the breadth of them around me. The sound opens up the space of the night and it feels huge. I try to move quietly, but I stumble, no longer sure where my body ends, and I tread clumsily over the frosty tussocks, testing each footstep before committing my full weight. I feel like I’m crossing a boat’s heaving deck, and wonder if it’s possible to become accustomed to the way the unseen ground meets the foot so unpredictably in the dark in the same way one gets ‘sea legs’ on a long voyage.

Once my eyes adjust and I settle in, I see it’s not completely dark. Everything is touched with a faint luminosity, the airglow of starlight diffused behind cloud. After the hectic orange of the streetlights, this silvered gloom feels like a cool hand laid gently on my forehead. I see in black and white, blocks and solids, big shapes, no detail. The gorse bushes are just dense black clumps, a bit blurred around the edges. The rounded hills above me slump heavily, darker against the charcoal grey of the sky.

The ground is fogged around my unseeable feet. I make myself keep walking out into the darkness and it feels like when I am faced with a blank sheet of drawing paper or when have written my way to the end of the last sentence where I knew what I was going to say, and know that I have to make myself keep on going, putting one word after another, because if I don’t I will just keep on circling those same well-lit streets of received thought and thinly veiled plagiarism. Any creative work is a walk into the dark, moving out towards uncertainty, trusting those quick darts of feeling, the almost physical twitch of recognition, the bubble-float dip that says ‘pay attention here’.

Walking is as much a way of moving thoughts along a path as the physical body. I keep stepping forwards, carrying my questions gently. There is something to discover, out here, in this wind-blown darkness. I have to wait, all senses open, observing what is to be observed, until my eyes adjust and I begin to see the subtle starlight behind the clouds.

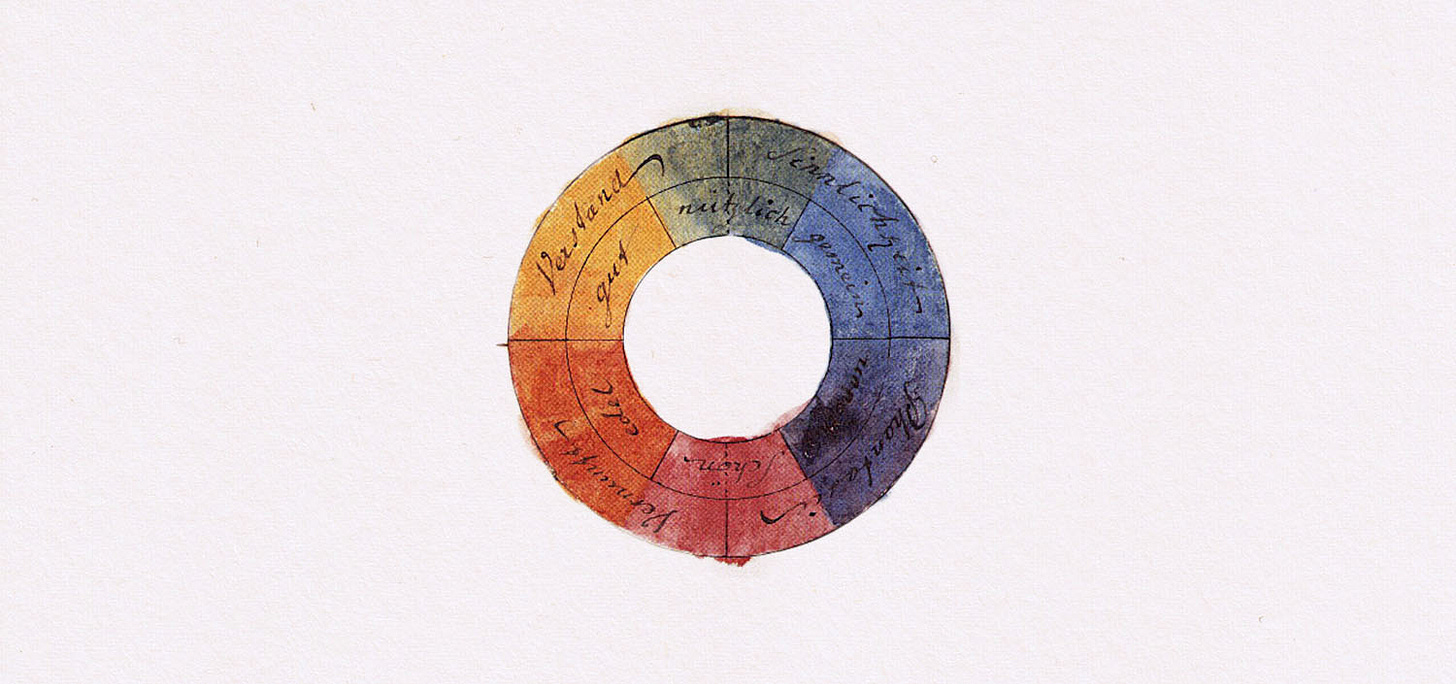

The poet and polymath Johann Wolfgang von Goethe knew how to observe what is to be observed, how to watch and wait until finally he understood something about darkness and light. Goethe did not see darkness as just an absence of light, as most of his contemporaries did. He believed darkness was an active agent, and that light and dark act as opposing forces, like the poles of a magnet, interacting with each other to create the phenomenon of colour.

Newton famously shone a narrow chink of light from a shuttered window through a prism to reveal how white light could be sliced up into the separate colours of the spectrum. Goethe, on the other hand, wanted to understand light in its wholeness, watching how light behaves as it moves in the living world, not shuttered away in darkened rooms and bent out of shape by prisms.

Noting that on a clear day the sky overhead is a brilliant blue, becoming paler as it nears the horizon, and that if you go up a mountain the sky becomes an even darker violet, Goethe understood that when we look at the sky we are seeing its true darkness illuminated by the sun’s light as it passes through the ‘turbid medium’ of the atmosphere.

On the other hand, on a clear day the sun overhead is a very pale yellow, almost white in clear skies. But as it sinks towards the horizon it becomes orange, even deep red, as the atmosphere thickens and so darkens the sunlight. As the sun rises again, the atmosphere that we see it through becomes thinner, so it loses these warm, rich colours. I had watched this phenomenon unfold myself with every winter dusk and dawn I had observed or filmed over these last few weeks.

As Goethe watched the changing sky, he understood that colour emerged from the shifting balance of darkness and light, and that both light and dark are necessary for colour to emerge: “Yellow is a light which has been dampened by darkness; blue is a darkness weakened by light.”

Goethe’s insight was that darkness isn’t something to be eliminated, ignored, fixed, or got rid of. It isn’t just an absence of light. It’s an active agent, interacting with light to produce the effects we see as colour.

Out here on the dark hill, I keep on walking, following the track upwards, and leave the lights of the village further and further behind me. The darkness feels as if it is swallowing me whole. As I crest the hill and drop into a shallow dip even the red pinpricks of light from the distant off-shore wind turbines vanish from view.

Still I keep on walking, away from the roads and houses, away from the people sleeping in their darkened homes, following the rough track out onto the open hill. And as I do, the big, dark night breathing over the moors no longer feels intimidating. I gulp in great lungfuls of the black air, drawing it into me, this active darkness that can twist warm yellow, orange, red, out of plain white light.

For most of my life, my mother has felt like a dark bruise on my heart. Darker still, denser and more hidden, is my shame. My mother was sick and I did not help her. I was young and frightened and angry, and more than that, I was cruel. I withheld the love she craved, cut and cut and cut again at the connection she hungered for, and gave her only the barest necessary access to my life. Of course she gave up and withdrew into herself. I had already done so years before. We lost each other a long time ago.

I see now that my numbness is not that I don’t feel grief for this loss. It’s that my grief is so old, has lived in me for so long that I no longer notice it. It runs right through me like dark matter, slow and heavy, shaping my form with its weight, yet unseeable. It’s a darkness my eyes have long since adjusted to.

But the darkness of grief is an active agent too. Poet Wendell Berry calls grief ‘the severe gift’. If I stay numb, protect myself from grief, difficulty, pain and distress, I wall myself off from joy and light and love too. The darkness enfolding me here is beautiful and spacious, and there is beauty and spaciousness in grief too. After all, it is an expression of love. I make my way slowly home again, carrying with me the severe gift of the dark hill, some kind of answer to the question I brought here with me.

Join the Life Raft Co-Working

If you’d like to share a supportive space for working on your creative projects, come and join our weekly Zoom session. We start with a quick hello, then leave our cameras on and work quietly together for an hour or so. A recording will be shared each Monday on the subscriber chat.

And if you’d like to read more…

The Clearing

"Perceptive…a reflection on art, life and the beauty to be found in things we can never fully understand." Times Literary Supplement

Beautiful resonant piece Samantha, thank you. I’ve been seeking out the dark too, of late. It is such a tender active force I’m finding.

You write beautifully. I was completely absorbed while reading this. And moved. Thank you.