This week’s post is the second half of the keynote presentation I gave to the DeathWrites RSE network at Glasgow University. If you missed it you can click here to read Part One.

We left off thinking about how the objects we use and live with are actually nodes in a vast web of connections, ideas, memories, places and people.

READY-TO-HAND OR PRESENT-AT-HAND

How many such objects do we make absent-minded use of throughout our day? Martin Heidegger’s famous analysis of tools in ‘Being and Time’ shows us that our usual way of dealing with the things we use daily is a kind of absent-minded reliance on them. He describes them as being ‘ready-to-hand’, disappearing behind their function as we handle and use them day to day. The object before us recedes and disappears into a ‘system’ of equipment.

Heidegger tells us that ‘equipment’ like this belongs in a system of relationships and uses that doesn’t really reveal itself until it fails or breaks. A broken tool suddenly erupts from its system of relations and is seen from outside of it. We see it as if for the first time. It becomes, in his terminology, ‘present-at-hand’.

BLACK BOXES

Bruno Latour also considers the object as embedded in a network in his Actor-Network Theory. He defines all entities as ‘actants’ defined entirely by their relations. Actants with relations that are firmly established and functioning smoothly, such that we take their interior for granted, he calls ‘black-boxes.’ A ‘black box’ is not like traditional ‘substance’, and it’s not quite like Heidegger’s ‘ready-to-hand’ tool either as it can be used to describe any ‘thing’, whether animate or inanimate, human or nonhuman. Our own body is a black box until something goes wrong with it.

Latour’s ‘black box’ has no unified essence and it can be opened at any time to reveal the teeming network of alliances at multiple scales of which it is composed. For example we might pick up a pebble on the beach and view it as a single entity, a ‘pebble’, but a geologist might reveal to us the volcanic activity or huge pressures of sedimentation and erosion of which it is comprised, opening the black box pebble to reveal that it contains yet more black boxes inside. It’s an illuminating exercise to try this yourself, from time to time, with the objects around you – your morning cup of coffee, the chair you’re sitting on, the shoes on your feet

You can go on opening black boxes indefinitely. Things keep retreating into other things in an infinite regress. According to Latour, there is no final layer of reality, only a web of relations. This way of understanding objects as continually coalescing and dissolving within a web of relationships breaks up old binaries of active subject and passive object, usually construed along the lines of human and world, and opens us to the rich complexity of things in themselves and our entanglement with them.

A thing according to Latour emerges as ‘real’ when it has effects on other things, not because of any integral reality in the thing itself. A thing is nothing more than the result of its effects on other entities. Things become more real the more connected they are to other things in the network and it is the density of these relationships that make a thing ‘real’. For Latour, what makes a black hole more real than a white unicorn is not that one exists in the world and the other one only in our minds, but that the black hole has more allies, a denser web of interactions and this web stretches beyond the human realm to become one of the forces that shapes the cosmos.

THINGS ARE GATHERINGS

Things and beings, subjects and objects, exist in and as a complex network of relations.

A thing is, etymologically, a gathering place. Placenames, as here in Orkney, Tingwall or Dingwall in the Highlands, and the Icelandic ‘Allthing’ parliament have all the same root meaning: a gathering point or place. In the Viking era a thing was a focus for law-making, religious activity, trade and exchange.

Every thing, then, is a gathering up, a point of coalescence, an aggregate. Even the things of which a thing is an aggregate, can themselves be understood as aggregates. There is no basement level of reality underneath.

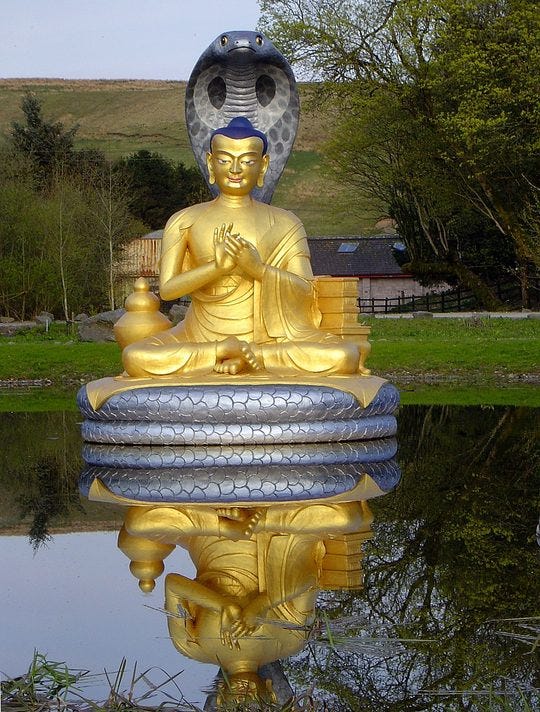

This is not a new realisation. The first century Indian philosopher Nagarjuna also argued that all things lack inherent existence or svabhava, which is translated as ‘own-being’. This central philosophical concept of the fundamental emptiness of form, or sunyata, forms the cornerstone of Mahayana Buddhist philosophy.

The sense of things as having some independent, solid, durable existence from their own side is, in the Mahayana tradition, understood as a conceptual projection onto a world of objects that actually lack it.

It’s an automatic but mistaken imposition that divides perceptual experience into a perceiving ‘subject’ and a separate world of ‘objects’.

According to the Mahayana tradition we have to work hard to train ourselves out of this habitual way of seeing things, through a mix of rigorous philosophical study, careful analysis and diligent meditation.

EMPTINESS

The aim of all this is not just to win an argument, but to eliminate this limited and automatic way of seeing things by means of specific meditative practices that strip away the seeming solidity of all things, all objects, including ourselves. Eventually, the way we actually perceive things will shift and we will be able to not just conceptualise, but actually see that all things continually arise and subside in an interdependent web of causes and conditions. This is called the direct realisation of ‘emptiness’.

So, having started out from objects we now find ourselves floating in the groundlessness of emptiness. Let’s take hold of our objects again and make our way back out of the philosophical undergrowth, back to the path, back to the things, these gathering-points, these objects that disappear behind their functions and re-appear when broken.

Let’s go back to my parents’ house to consider another thing I wrote about in The Clearing: my mother’s piano.

Upstairs in the lounge is the very last piece of furniture waiting to be moved. My mother’s piano still stands by the window in the corner of the room, exactly where it has stood for forty-five years. It is my piano now, my mother’s legacy, the only object named in her will to be left specifically to me. I think she had decided it should be mine because at one time I had played it often, if badly. But I haven’t played for years now and I have no space for it in my small flat, so it sits here while I try to figure out what to do with it. It’s a baby grand, with a warm chestnut veneer and chipped ivory keys. It hasn’t been tuned in years and isn’t a fancy make. So although it’s undeniably a handsome piece of furniture, it’s also a big, out-of-tune piano that nobody seems to want. But I can’t just dump it. It’s my mother’s piano and she has left it to me. I am ungrateful, I know. Her gesture was well meant. But it feels more like a problem than a gift.

Three tufts of rotted carpet remain under the piano’s feet where I had cut holes in it so the clearance men could take up the rug without shifting it. The piano stands alone, everything around it gone. Its elegance seems out of place now, like a bewildered antelope in a bare zoo enclosure. How much the arrival of this gracious instrument must have meant to my mother I can only guess. She must have felt she’d come a long way from her girlhood in that colliery village.

Sometimes I’d pull out some of my mother’s old sheet music and try to play the pieces I could just remember her playing, a long time ago. I was never quite sure whether playing them made me feel closer to her or farther away. The piano seems to stand for all that my mother might have been, for the young woman she had been, once, before I knew her. Before everything changed. Maybe that’s why she has given it to me, to remind me of who she once was, to share something with me that had once been precious to her, some far-off music from her life before, sounding out from the dark space of a long-forgotten evening.

THE ORPHANED OBJECT

The broken thing, the ownerless thing, the thing once loved by someone who is now gone, the thing nobody knows how to work anymore, the thing whose function is now obscure, is suddenly seen from outside the system of relations and uses that once defined it. We need to learn how to understand it all over again, build a new system of relations around it. This is a kind of mending. The object becomes a catalyst for the make-do-and mend work of grieving.

I wrote in The Clearing about making one final, short visit to my parents’ house to say goodbye:

I open the door to my father’s workroom. It’s now just a bare and shabby box with a low ceiling and bars at the window. All signs of him are gone now, I think. But then I spot a piece of cable glued firmly into a hole cut into one of the windowpanes so he could connect to an antenna on the roof, a clue that the new owners will not recognise. The faint pattern of 1950s wallpaper still shows through the whitewash my father hastily painted over it decades ago. I turn to leave but my eye fixes on the soft brown smudge on the wall around the light switch, left by the repeated passing of his hand, year after year. The family who move in here will see only a grubby mark. But I see my father’s hand reaching for the light switch as he leaves my mother sleeping in front of the television and goes into his room, turns on his radios, puts on his headphones and listens to the crackle and hiss of the universe, builds another model plane, tests the balance of its wingspan on a fingertip.

Memory is not just in the mind. It lives in actual places, in actual things. It sits in empty chairs and in stained and worn carpets and smudged walls and light switches. I stand close to the wall and rest my own fingertips against the mark my father’s touch had left, a final intimacy, the closest I will ever get to his physical presence again. I can almost smell him. A sudden ambush of grief falls upon me, heavy as surf. Pinned down by it, I lean my forehead to the grease-marked wall, sobbing hard and repeating ‘I’m sorry. I’m sorry I didn’t talk to you. I didn’t help you enough. I’m so sorry.’

The wave leaves as swiftly as it came. I wipe my eyes, leave the room and close the door behind me.

THE REPAIR SHOP OF THE HEART

It feels like an affront that the smudge should still be there while the hand that made it is gone forever. My own grief erupts in a realisation that this small thing, like so many others from my parents’ lives, has come loose from its web of relations and will not be understood by the new owners when they move in. When we encounter an object that ignites our grief it’s because we have a felt sense of those broken connections. It feels like a phantom limb that gives us pain even though it’s not there anymore.

The thing stripped of half its relations, adrift in the world, becomes emblematic of our own stripped-down-ness, our feeling of amputation, our grief.

It becomes less real and with it, our loved one recedes as well.

This is why we keep things that remind us of those we have lost. And this, I think, is why we write about them, show them to people, share and reshare the stories about them. The act of writing about these things, of telling their stories and showing them, is an act of repair and mending. It rebuilds a network of new relations so these things become more real again, and by extension, the people who once owned or used or made them remain entangled in the world by these things and so stay real for us even though they are no longer alive.

I’m sure I’m not the only one who has quietly sniffled through a few episodes of The Repair Shop. We are watching people repair stories and relationships, rebuilding these webs as much as the objects themselves. The emotional charge around this process is reverent, tender, sorrowful and yet often joyful too. Through the work of care, attention and storytelling the object is no longer bereft. The new custodian is also mended.

We do the mending work of grief when we take the bereft object and reweave its web of relations, stories, and uses, and keep it and its past owner ‘real’.

I propose that we understand objects as gatherings that record. They record the web of relationships that gives them meaning and we mend that web, and ourselves, by telling and retelling their stories.

Sam

References:

Latour, B. 2007. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor Network Theory (Clarendon Lectures in Management Studies) Oxford: Oxfrod University Press

Latour. B. 1993. [trans. Porter, C] We Have Never Been Modern, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

Heidegger, M. 2009. Being and Time. Translated and edited by T. Macquarrie and E. Robinson. Oxford: Blackwell.

Westerhoff, J. 2009. Nagarjuna’s Madhyamaka: A Philosophical Introduction, Oford University Pre

Copyright (C) *|CURRENT_YEAR|* *|LIST:COMPANY|*. All rights reserved.

*|IFNOT:ARCHIVE_PAGE|**|LIST:DESCRIPTION|**|END:IF|*

Our mailing address is:

*|IFNOT:ARCHIVE_PAGE|**|HTML:LIST_ADDRESS_HTML|**|END:IF|*

Want to change how you receive these emails?

You can update your preferences or unsubscribe