One bruised apple: Or, how art stops time

One of the rich pleasures of working with my coaching clients is the conversations that develop, unhurriedly, in our written correspondence. These remind me how creative work is essentially collaborative, even if it might not seem so on the surface. Connecting with someone else’s creative world always sparks our own too, and working in complete isolation is very hard to sustain.

Books are also a source of creative companionship and I often find I make suggestions to a client for a book they might enjoy. When I do, I always end up reaching it down from my bookshelf and re-igniting my own enthusiasm for that writer’s work.

Lia Purpura is an essayist and poet who is not as well known in the UK as in her own country, the US. I have found myself mentioning her a couple of times recently in conversations about the relationship between art and time; how art can contain time, how it can capture and dilate a single moment, or record its swift passing.

Purpura has published several volumes of poetry and three fine collections of lyric essays. She uses the essay form as a tool to excavate deep into what Wordsworth termed ‘spots of time’ or Woolf called ‘moments of being’, unfolding and laying out all the ramifications and interconnections, both internal and external, or a single moment. The movement in Purpura’s essays isn’t a linear, plot-driven narrative story as such. They are associative, elliptical, nonlinear, and invite a slow reading i same way poetry does.

In one essay in Rough Likeness entitled ‘Try our Delicious Pizza’, Purpura reflects on those moments when an inexplicable and sudden sadness arises. Instead of moving onto the next event, she holds us there in that moment of sadness, prompted, in her first example, by the sight of a fully-loaded coal train. “This sadness”, she notes “surprises. It’s hosted very specifically in some forms and not others” She gives examples of other such occasions; the sight of a caged-in bridge over a motorway at dawn, or:

“Apples: the fate of certain ones. The other day, a grocery clerk was unpacking Braeburns from Washington state, gorgeous fruits with shiny yellow and red spin-art skins – and he dropped one. He picked it up and tossed it in the box at his feet. That’s all it took. Especially the ‘thunk’. To grow, to be picked, to travel so far – to end up discarded in the store, that very last port before purchase. I don’t know why this moment of sadness couldn’t be fixed by adjusting perspective (towards the bright side: see all the apples that did make it safely!) It didn’t allow for misperception (maybe that’s the wipe-and-restock pile) nor did it support much hopeful conjecture (don’t worry lady, those go to the homeless shelter). All the efforts of sun, rain, tilling, all the stacking and storing and driving, all the picking by hand. And after a long day, all the heads on bare mattresses, wrists aching, necks sore, pesticides swallowed, crap wages in pockets – made for a particular density of sadness, just the size of a perfect Braeburn.”

However, the sadness Purpura refers to here is not a debilitating one. It is one to be lingered with, examined thoroughly. “How generous sadness is” she says. “How capacious”.

“Mostly, though, how startling – so that just when one’s settled into the moment, say on a train to visit one’s parents, book out, orange peeled, coffee balanced and cooling, there it is, a swift visitation; coal trains on the station offering the sundered, ruined hearts of mountains. Brief five o’clock light. A frayed cuff of a seat mate. Snowy egrets in a marsh the train passes. Some birds stilled in the rushes, others fishing in mud. The mud rainbowed with oil.

One spends the ride containing it all.”

Purpura does not recount a narrative; she gives us an experience and we make of it what we will. Her minutely keen observation takes a cross section of an instant, rather than moving horizontally through time. This slows time in a rich way, as something to be savoured.

In an interview Purpura talks about “very fully staying with a small moment, an errant thought-that-hit, and writing into the density of that moment, small as it was”, a moment “otherwise lost if not attended to.”

Purpura’s method is to sink into these deeply fertile but hard-to-pin-down moments. Although she is writing about her own experience, she insists that her writing is not memoir as such and prefers the tentative, epistolary, essay form. This, she feels serves her sensibility, because there is the sense of presence of the author. She wants her essays to show her thinking through a problem right there on the page, and in this they bear the marks of the maker the way a hand-made pot does. She talks of valuing:

“Smudges of a certain sort. Fingerprints. Breath. Precision, machine-tooled writing, writing that gets the job done, doesn’t allow for a little dirt under its nails…that’s not what feels most achingly human.”

In stilling the onward rush of event to plumb the moment of consciousness, Purpura shows us how we exist in a mesh, how what is outside reaches into us, and also how reach outside ourselves, how things connect and go unfolding outwards and inwards. Her writing dissects such moments of interpenetration…"to feel the exchange across borders”.

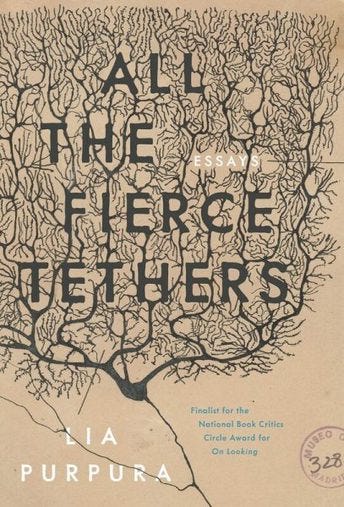

I have well-thumbed copies of Rough Likeness and On Looking on my bookshelves, and was delighted to discover that she has in the meantime published a new collection I haven’t read yet in All the Fierce Tethers - now on order!

For a different perspective on how things connect and interpenetrate you might like to read my posts on "Things and Gatherings" parts One and Two.

May all your Braeburns be unbruised,

Sam