Writing a memoir? I could tell you stories...

If you're writing from your own life, I'm here to say this once and for all: your memoir is not about you.

Several of my creative coaching clients are working on a writing project that’s drawn from their own life experiences.

And, just as I was when I was, when writing my own book The Clearing, at a certain point they are somewhat taken aback to realise that they are writing….a memoir.

Memoir is a word that comes with a lot of baggage, much of it unhelpful. It’s not surprising that my clients fall prey to moments of self-doubt and begin to question the validity of telling their own stories.

So if you are writing from your own life I’m here to say this, once and for all:

YOUR MEMOIR IS NOT ABOUT YOU

It is not a sign of self-absorption. Memoir is a form of inquiry. It’s a way of examining memory and experience to find something out and to share that with others.

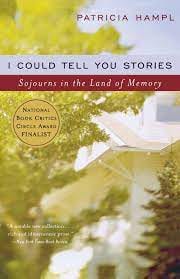

I’m not the only one who makes this case for memoir. Writer and educator Patricia Hampl does too in “I Could Tell You Stories: Sojourns in the Land of Memory”:

“Some people think of autobiographical writing as the precious occupation of the unusually self-absorbed. Couldn’t the same accusation be hurled at the lyric poet, at a novelist – at anyone with the audacity to present a personal point of view?

True memoir is written like all literature, in an attempt to find not only a self but a world. The self-absorption that seems to be the impetus and embarrassment of autobiography turns into (perhaps always was) a hunger for the world.”

We increasingly find ourselves living at one remove from our locality, and often from our friends and relatives too, accessing the world through our electronic devices.

In “Then, Again: The Art of Time in Memoir”, Sven Birkerts suggests that memoir is a way to give voice to how it is to be alive in this dense and complicated world.

Memoir models for us a way to reflect on and make sense of our experience, to seek pattern, coherence and meaning. When it’s done well, this resonates with the reader’s own experience. He says:

“The point – the glory – of memoir is that it anchors its authority in the actual life; it is a modelling of the process of creative self-inquiry as it is applied to the stuff of life experience.”

MEMOIR ISN’T AUTOBIOGRAPHY

Memoir has a deeper purpose, then. It isn’t just re-enacting the author’s past. Memoir works to discover the non-sequential connections that allow these experiences to make a larger sense.

This means that time is always complicated in memoir. There are always at least two ‘nows’ – the ‘now’ of writing and the ‘now’ of what is being written about – often there are many more. Birkerts explains that the memoirist needs to keep at least two things going on at once:

“I need to give the reader both the unprocessed feeling of the world as I saw it then and a reflective vantage point that incorporates or suggests that these events made a different kind of sense over time. This is the transformation that, if done well, absolves the memoiristic reflection from the charge of self-involved navel-gazing. What makes the difference is not only the fact of self-reflective awareness, but the conversion of private into public by way of a narrative compelling the interest and engagement of the reader.”

Memoir documents a mind in the act of wringing meaning out of perception and memory, assembling the chaotic nature of experience into some shape that has relevance to readers.

This, I think, is the fundamental difference between memoir and autobiography. Memoir is less concerned with the sequence of events in a life than with its shape. As Birkerts says::

“Events are necessarily filtered by the memory and recounted in ways that reflect understanding and interpretation…and because we come to our insights more by way of thematic association than chronology, using hindsight to pick the lock of the then, the structure of the work seldom follows the A-B-C of logical sequence.”

TIME TRAVELLING IN MEMOIR

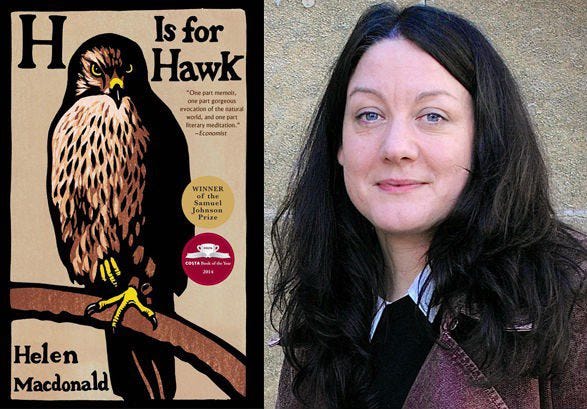

Here’s a good example: MacDonald’s “H is for Hawk” is an account of her training a young goshawk as a way to deal with her grief over the sudden death of her father. Its structure does not follow of chronological sequence. Time is elastic, and Macdonald shuttles freely back and forth between personal narrative, intensely observed nature writing, and a biography of another writer who also trained a goshawk, T.H. White.

In the opening section of the book, as MacDonald is walking in some woods in search of wild goshawks, she is suddenly pitched, by the sight of a sparrowhawk, into the past:

“I felt my small-girl fingers hooked through plastic chain-link and the weight of East German binoculars around my neck.”

In this brief vignette she deftly outlines her tender relationship with her father. Then, we are quickly brought back again, through the vividness of her detailed observation, to the moment of her walk in the woods to see goshawks, and then abruptly flung forward to the moment, three weeks later, when she learns of her father’s sudden death.

The trigger this time is not the sight of a sparrowhawk but a piece of moss she picked up on that walk, that sits on a shelf by the phone when she hears the news. The moss, which can survive “just about anything the world throws at it” by going dormant, is a symbol of patience and tenacity that takes on new meaning now. As her story unfolds, we see how Macdonald herself goes ‘dormant’ in a sense. Shocked and grieving, she withdraws from human interaction into the world of her goshawk for several months, to eventually re-emerge into the sustaining warmth of human companionship.

As Hampl says:

“Memoir is the intersection of narration and reflection, or storytelling and essay writing. It can present story and consider the meaning of the story. Memoir is a peculiarly open form, inviting broken and incomplete images, half recollected fragments, all the mass (and mess) of detail.”

So don’t shy from the word memoir, as a writer or as a reader. It’s a nimble, thought-provoking genre as varied as the people who write it.

And before I sign off, I’d just like to say thank you for subscribing and for reading my. I really hope you find my missives informative and interesting. If there are topics you’d particularly like to hear more about do let me know! I’d love to hear from you.

Sam

P.S. If you’d like a bit more on this topic here’s another short article I wrote about memoir writing for the Scottish Book Trust website.