'Making a Handaxe': a knot in time.

A conversation with archaeologist, artist and writer Mark Edmonds

This week’s newsletter is a conversation I shared with archaeologist, writer and artist Mark Edmonds. He came to my studio at the weekend to talk about his new book "Making a Handaxe", bringing with him an object of contemplation and conversation: an exquisitely shaped flint handaxe from the Lower Paeolithic.

You can listen to the audio of our conversation here, or, if you prefer to read, scroll down to find the transcript of our conversation below.

Prof. Mark Edmonds visiting my studio, holding a flint handaxe that was made somewhere between 375,000 and 425,000 years ago.

TRANSCRIPT:

Samantha Clark:

So thanks for coming along today, Mark. I wanted to talk to you about your wonderful book, ‘Making a Handaxe’ which was published in 2022. And I was interested in how you came to archaeology because you are a man of many talents. You are a professor emeritus of archaeology, an artist, a writer, poet, curator, among other things. So, how did you come to archaeology?

Mark Edmonds:

It's a good question. I came to archaeology through making, through an interest in art and art practice. This is way back in the 70s, and I became fascinated by archaeological objects. I was invited to come in and do some work in a museum. This was down in Wiltshire years and years ago to make models for their displays. And at that point, I knew nothing about archaeology.

But I just found myself going back again and again to spend time with the collections, particularly drawing objects and just becoming fascinated particularly with the stone objects that they had in vast numbers in boxes in the back, and I kind of fell into it from that.

I think one of the things that I gravitated towards was the fact that archaeology is this really lovely mixture of physical, materially driven, practical work, really bodily directed, and at the same time, it's a very creative, very imaginative practice. Because you're dealing with materials, you're dealing with the physical reality of places, but you're always trying to imagine what those things what those places may have been like 100 years, 1000 years, 10,000 years or 100,000 years ago, which is just a lovely stretch to the mind, really.

So it was that combination of things that I kind of fell into. I certainly didn't plan at that point to have a career in it, but so it's turned out. And certainly over the last 10-15 years, for me, it's been an act of rediscovering a lot of things that attracted me in the first place, particularly the idea of trying to use more artistic practice to get at the things that I think are really interesting or important or exciting, about archaeological materials.

SC:

And the central fascination of your book ‘Making a Handaxe’ is with a specific handaxe that you come at from so many different angles. You use poetry, you use personal narrative, and then there's the more kind of discursive writing and also there's the work that you've done with these beautiful engravings that you’ve re- used.

ME:

Yes, for a long time working as an archaeologist, particularly teaching, like any discipline, archaeology has a particular way of doing things. I mean, it's in the nature of the word ‘discipline’, that there are ways of approaching materials or times, there are ways of writing about the past, which are very, very conventional. There is a particular kind of structure to the way that most archaeological investigations work, and for years I've always found myself getting very frustrated that the way that we approach material as archaeologists misses what's exciting or important or vital about it.

And for me, that means that we need to experiment a lot more with different ways of writing, different ways of using imagery, different ways of using what in other settings we would call installations or performance. And for a long time I’ve felt that there are many ways in which artists work, the practice of artists working with image-making, working with materials or working with installations and performance that seem to be more effective at getting at what's important about their material.

So yes, there's perhaps a bit of frustration at not really being able to catch what matters in conventional archaeological terms, but recognising that there are loads of writers and artists out there who've been doing this for years, and just trying to push my work to see if that's possible.

SC:

And you have this beautiful object here that you've brought. Tell us a bit about it.

ME:

Well, I brought along this little handaxe which is in the book. And, you know, a lot of the work I do is looking at materials, objects and landscape. But for most of my career I haven't gone back further than about 10,000 years. And a good deal of my work has been about the Neolithic, the period of the first farmers. This little piece of stone, which is flint, a very glassy rock that's formed and found in the chalk, this is much older, and this particular one is probably somewhere between about 375 and 425,000 years old. So, at its upper limit, it's getting on for half a million years old.

SC:

Wow…

And yet it's held in the hand. Made by a hand very similar to ours. You can see how it just invites the hand to hold it. It fits the palm so beautifully, and it has a twist to it.

ME:

Yes, this one's relatively small. Hand axes come in all sorts of different shapes and sizes and the oldest ones we have, which can look very similar to this go back to about 1.6 to 1.7 million years ago. And I can't quite get my head around that, because just holding an object like this and realising the depth of time is almost abyssal, between then and now, when this was made and used. And now here it is in our hands. It's a very simple oval when you look at it just lying flat in your palm, and yes, it does fit the palm. Quite, quite beautiful.

SC:

Yes, you use that lovely phrase in the book, of ‘the space between two hands in prayer,’ the gap between the two palms.

ME:

It just does just fit very neatly, and it's covered in the little scars from its making. So you know, it's an object that carries with it a very good, very sharp record of how it's been made.

SC:

Something you touch on in the book as well as these many different kinds of time. Just like you're talking about the span of time between it's making and now and then there's also that duration of hand-axes being made and used for enormous span of time, and then also this instant, that it's shape records, of a single blow, all these different kinds of textures of time that are kind of held in this object. That's what makes it a kind of a meditation on time.

ME: You're absolutely right. I think that's one of the things that makes objects like this, I think, so special. Quite a lot of things keep secrets. It's very difficult to see how something's been made, or to get some sense of what was involved in its making. With things like flint artefacts, and particularly with hand axes that have basically been struck repeatedly, often with great degrees of skill, and sometimes very careful trimming to produce a flaked object, in this case a sort of rough oval shape, and across both faces you can see ridges that mark the line of the flakes that have been knocked off of the surface to give this thing it's form, so yes, on the one hand, it's a piece of deep time. And deep time is something that, from the Victorian period onwards, since geologists started to open things up, we have difficulty in contemplating.

But at the same time, when you work your way around the edges and the faces of this object, you're getting individual moments when somebody raised it to look down the line, placed it on one hand, maybe against their thigh, and then struck it with a hammer or a stone, and, looking at some of these scars, they probably used something like dense bone or antler, to very carefully remove flakes and give this thing its shape. So there's several different senses of time, as you say.

SC:

Yes, you mention in the book, the point in our story where “when humanity stepped out of the eternal present, when making opened us up to different kinds of time”. And there's also the geological formation of the flint, as well. You talk about that too.

ME:

Well, yes, I mean, that's the thing. You've got the time of the making, the time that's involved in in creating something like this, and it may be what we would regard as half an hour, maybe a little more, maybe a little less. And then you've got the time between then and now, which we might measure in terms of hundreds of 1000s of years, but the flint itself is formed in the chalk. So it's part of the Cretaceous, which ended around 66 million years ago. So there are different kinds of time that you can trace even in the materials. It's also made of elements such as silicon, magnesium, a bit of iron, that gives it its colour. And those elements are formed in a different scale of time altogether. That takes us back several billion years to what people call “Hadean” time. And then the names as you go further out become incredible and very, very poetic.

Trying to get your head around the way in which the solar system is formed, the way in which stars create matter, create elements, scientists for as long as you could possibly go back have turned to poetic language to try and capture that.

So that's all there in this object.

SC:

There's a passage in the book where you're imaginatively re inhabiting the moment when the tool was used, and that they were used and then just discarded. And you use the word “knot”, which is a really evocative way of explaining this object. It's like a knot, a gathering. Everything comes together for this moment, in this object and it's making, its use, and then it's discarded and that moment has passed on. But we come back to it hundreds of thousands of years later, and even now, when we're sitting here, we’re looking at it, we're both looking at this handaxe the whole time. We're talking and you're turning it in your hand and we can't take our eyes off it. It is a knot, isn't it, that draws us in?

ME:

Absolutely. This is a piece of the lower Palaeolithic. The oldest stone age that we have. I’m just trying to get my head around what appears to be a couple of really big paradoxes or contradictions. When I look at this object when I turn it in my hand, I can see that it's been made by somebody with a real understanding of the material. There's a real skill in the simple act of flaking that has been exercised here to create the shape, and it has a very curious sinuous line to it that runs around the edges when you look at it, which is quite deliberate. So there's intention. There's creative responses to the material. There's a negotiation with this particular piece of stone to make a very distinctive shaped object. Design intention, craft care skill, these are all absolutely fundamental words to catch the process of making.

And it's not made by a human, or by what we would call a human. It's not made by Homo sapiens sapiens. It’s made by one of our ancestors. And what I really like about that what I find still shocking is we kind of still live with the legacy of the Victorians who put homo sapiens Sapiens on a pedestal. For them, they were the winners of the evolutionary story, if you like. And there were so many things that the Victorians said were unique to humanity, to modern Homo sapiens. And yet, when you look at an object like this, you realise that there are so many things that we think of as being essential to being human, that were there already, that this is an object that's made through a creative act, by somebody who has reflected on it, thought about it, and used a great deal of skill, skill which they've learned. But before ‘we’ came blinking into the light.

SC:

And a lot of these tools are older than language. I love the analogy you make that they look like tongues. They look like tongues, yes! And that language might have kind of gathered around them, and around the making of them perhaps as well.

ME:

There were stone tools across the last two, 3 million years that had been made by our ancestors in one shape or form. But it's when you get to hand axes at around about 1.6, 1.7 million years ago (and probably next week, we'll find it goes back a bit further) that you start to see the emergence of people engaging with material to make a particular form. Form becomes something that people reflect on, they think about and they try to realise.

Sometimes it's done well, often it's not. I'm not sure it's always that important. But these are the first objects that we see, objects that have survived, where you can trace people reflecting on their relationship with material. And you just think, well, is that indicating that there's a change in the way in which our ancestors are actually thinking about their relationshi to the material world around them? Starting to not just use things, but think about things and think through objects, through making, long before modern humans emerge?

Our ancestors are beginning to use the materials around them to think about the world, think about their relation to it, and to make statements, sometimes to themselves, perhaps to others as well. So that brings up, as you say, the question of language. There's no necessity I think, to have language in order to know how to make a handaxe. You can learn how to make them by watching people. You can learn by getting grunts of approval, or shakes of a head. So there's no special technical vocabulary that would be required. But I can't help wondering whether it's actually the other way around. It's not that you need language to make something like this. It’s when you start making something like this you need language to make sense of it. So, if you're making objects where the form matters, where exercising skill matters, then you're making something that people might want to talk about. So yeah, maybe that process of making is actually one of the things that encourages the development of language. When that happens, I have no idea.

SC:

But you know, when you're doing a particularly tricky task with your fingers, your tongue pokes out, it starts to get involved!

One of the things that's really striking in the book is these absolutely gorgeous illustrations that you have as well, that you've drawn from the engravings that you've found.

ME:

Well, the book is primarily about a particular handaxe one that was found in the gravels of Oxfordshire. Most of these things come out of gravel deposits in the Thames Valley, and other rivers too. And it belongs to a friend of mine, Alan Garner the writer. And years ago, when we were working on another project, we were talking about this object and he just said, 'you know, I've always thought that this might stimulate a book but it never has and it never will.' And so that was a bit of a challenge!

So I started thinking about how to write about that particular handaxe, slightly larger than the one I'm holding at the moment. And one of the things I found myself doing was going back to the 19th century literature, because handaxes are effectively a Victorian invention. I mean, they've been picked up, looked after, placed in the rafters, placed in people's fireplaces to ward off lightning, used for centuries. So, they've been objects that people are fastened upon for centuries, if not for 1000s of years.

But it's really only in the 19th century, the second half of the 19th century when antiquarianism is turning into archaeology that people start to recognise that objects like this are being found deep, deep underground. And it's things like roadbuilding, quarrying for stone, for gravel, for brick earth, industrial and urban expansion and mining ore that opens massive windows into the history of the Earth. And it's around about that time when people are beginning to recognise, ‘Actually, no, it didn't form in 4004 BC, on October the 23rd at 9.15. The earth is much older.’ And as geologists started to track the slow sedimentary process, the formation and the reworking of the earth, so these things started to turn up at great depth.

And reading through the late Victorian literature, basically the second half of the 19th century, you're seeing people starting to recognise first of all, that these are artefacts that have been made. But secondly, they belong to an order of time which a generation before no one thought was possible, that didn't exist.

So there's one book in particular, which I found myself going back to which is “The stone implements, weapons and ornaments of Great Britain” by Sir John Evans, published first in 1872, republished in 1879. And it's just this huge doorstop of a book which catalogues stone artefacts from what we would say is the entire range of prehistory from the Palaeolithic to the Bronze Age, with descriptions of where they've been found, and in particular descriptions of who owns them, whose collections they are part of or whose collections they used to be part of, before they became part of John Evans’ collection. They're absolutely obsessed with with documenting where things are from, but also who's had them. So there's kind of biographical time built into many of these objects as well, or written into them.

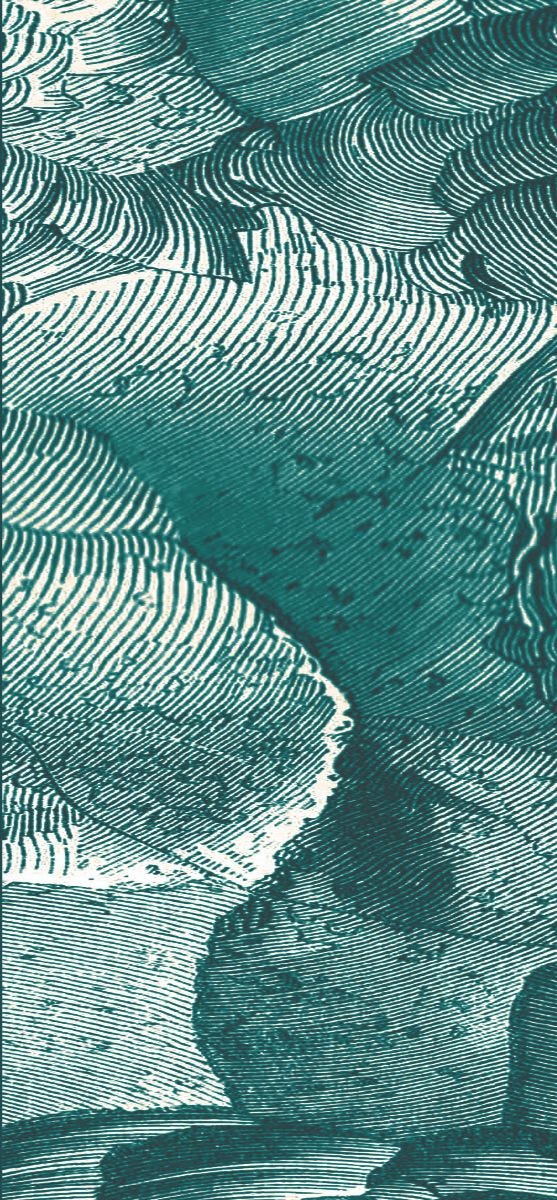

But Evans's book, which catalogues these things, has the most extraordinary engravings, They were done in Bouverie Street, London, by a set of engravers, among them Joseph Swain, who were just superlative. They're extraordinary woodblocks, which are just cut with the most remarkable lines. I mean, we can do 3D models now, and we can do all sorts of different kinds of photogrammetry to capture the contours of objects, but the engravings are just the best.

SC:

So exquisite, and they describe the forms so clearly.

ME:

Evans' book is a kind of seminal text that most archaeologists who look at stone tools would always go back to. Many will have it on their shelves. But I kind of rediscovered it with this project.

And two things were really striking. First of all, reading it, not just to sort of get a sense of the milieu of antiquarian writing in the late 19th century, or the nature of the objects and their provenance, but seeing somebody trying to come to terms with deep time. There are passages of the book where Evans imagines standing on Beachy Head and being able to see across land all the way through to what we would know as 'the continent' and becoming aware of how much things have changed and over what kind of timescales.

But the other is these engravings and quite by chance, as I was going through, I started to pull in my focus on the engravings and discovered that an immaculately carved wood block engraving over the face of a handaxe, when you get up close, loses all sense of scale and becomes a landscape.

Now these objects, which are in his book, are reported as having been discovered in river valleys which have been formed by several ice ages, that cycle of ice expanding and then contracting back up towards the north, the waters cascading down and carrying all this material into the gravels, including things like this handaxe, but then when you look at the engravings in detail, it looks like those landscapes! You can see all the water coursing across. You can see all sorts of features, like the turbulent flow of water. So that loss of a sense of scale, or the idea that scales shift backwards and forwards, you can see that in the object itself, but you can really see it the engravings.

SC:

Yes, and you also make a point, which I think is quite pertinent, that the activity of engraving is a haptic process. You're searching, you're carving, and that it's work of the hand, it's work of the hand to interpret a work of the hand. I mean, there's an intelligence of the hand, that we can see when we're looking at those engravings that is helping us to understand what the object is.

ME: I think there's a really profound intelligence of the hand. I find it difficult to imagine that the people who did the carvings of those woodblocks didn't understand how these objects were made. Somebody, maybe Evans himself, may well have told them, may even have sat there and made some to show them.

But there's an intelligence about the process of working stone, which you can see in the engravings. And again, it's the same thing, it's how do you push against the grain? How much pressure do you apply? Do you work from the hand or do you have the pressure coming on down through the shoulder? Yeah, all those things which are absolutely central to the process of wood carving for engravings and indeed other kinds of carving are also essential to the way you work the stone. So they communicate a huge amount about the process, the practice.

SC:

Wonderful. Would you like to read a bit?

ME:

I'll just read a short passage that relates back to something we were just talking about it about that sense of looking in and looking close at the surface of one of these objects or looking at the engravings themselves and losing yourself in different scales of space and time.

“A focus on the outline gives way to the detail of a soft and shallow scar. Ripples hang like gathered silk between the ridges, the curves, drawing you in and down. You travel in from the edge of the stone, looking back at jutting crags while the water rolls down slope. The valleys open out contours relaxing towards the level as they descend, scoured ground waiting for the green. There is ice still on the horizon.”

So again, I think that it doesn't take much to step away from the object itself to the kinds of processes that object has been caught up in that the more I look at something like this particular handaxe and indeed many others. The more I find in the record of flaking across its surfaces, record the way in which landscapes have been worked and reworked, over time, over the long term of the Ice Age cycles.

SC:

And you mention that these objects are at the same time beautiful and also sublime. I think at the very end of the book, you use the word ‘terrifying’, that the sort of dizzying sense of vast expanses of time is an experience of the sublime.

ME:

Absolutely, I mean, I came into archaeology because I was interested in making, and in particular I was interested in working with stone and in sculpture, making, working with different kinds of stone, which set up their own kinds of concerns in terms of how you work them.

So the making of flint artefacts is something that I've taken a particular interest in. But one of the things that I found really striking about this object, this handaxe, is that in one sense, looking at the scars across both faces, I know how it's made. I can turn it in my hand and I can imagine the way that the thing was being held, the way it was being struck, where somebody struck it with a certain degree of force. Other places where you can see it's been very, very gently worked, and I can hear it, I can hear the hiss as little flakes come off. I can hear the tinkle of them when they land on the ground.

But with all that, which makes it sound incredibly familiar, there's something else about this, which I still struggle to get my head around. And I surprised myself actually when I was working on this book, as one of the things that's always a struggle in archaeology is writing about the past and giving the past its own character, its own time in its own place, rather than just making it sound just like us, just like now. And the thing that surprised me with this object is the more I looked at it, the more I tried to understand it, the more difficult it became; the possibility that it's been made by a different kind of human being, and what would it be, to be that human being, who has a very different relationship to the world, who may be, as we would regard it, as much a part of nature as a part of history, but still, nonetheless has a very strong sense of culture, a particular way of engaging with the world? And just being able to try and contemplate the lengths of time over which the flint was formed, the stone was shaped and used.

And then what's happened to it ever since the movement of it through the passage of water, and then all the different hands that it's been in, I mean, this the one I'm holding at the moment has a small label on it. It's been part of a collection. But I have no idea what collection. Somewhere there'll be a written record, somewhere written by hand will be details of where this thing was from and where it was found, but I don't know that.

So it induces a kind of vertigo. It encourages or forces me to contemplate scales of time, and scales of change and the character of the landscape, changes in the character of humanity which are, yeah, terrifying. There's a kind of vertigo that you get, absolutely.

When you stop and think about all the different kinds of time that caught up in that small stone.

I hope you enjoyed this conversation as much as I did. And if you'd like your own copy of Mark's book you can find it here.

Sam