There's a difference between looking and seeing...

Interview with Orkney based wildlife cameraman Raymond Besant

This week I’m delighted to share a wonderfully thoughtful conversation I had with Orkney-based freelance wildlife cameraman and photographer Raymond Besant.

I’ve admired Raymond’s work for a long time. Orkney being a small place, we’ve met a on a number of occasions, but it was a pleasure to sit down and have a proper conversation with him about his work, how he sees his role as a wildlife cameraman, and the need for courtesy in our interactions with the wildlife we seek to capture with our cameras.

His beautiful book “Naturally Orkney 2: Coastlines” is available here:

If you'd like to listen while you're out for a walk somewhere, you’ll find the audio on Mixcloud here, Or you can watch the video recording of our conversation in full here.

But if you'd like to see some of Raymond's gorgeous photographs of Orkney's coast and its wildlife, please read on...contact Raymond for prints of these at raybesant@gmail.com

Samantha Clark:

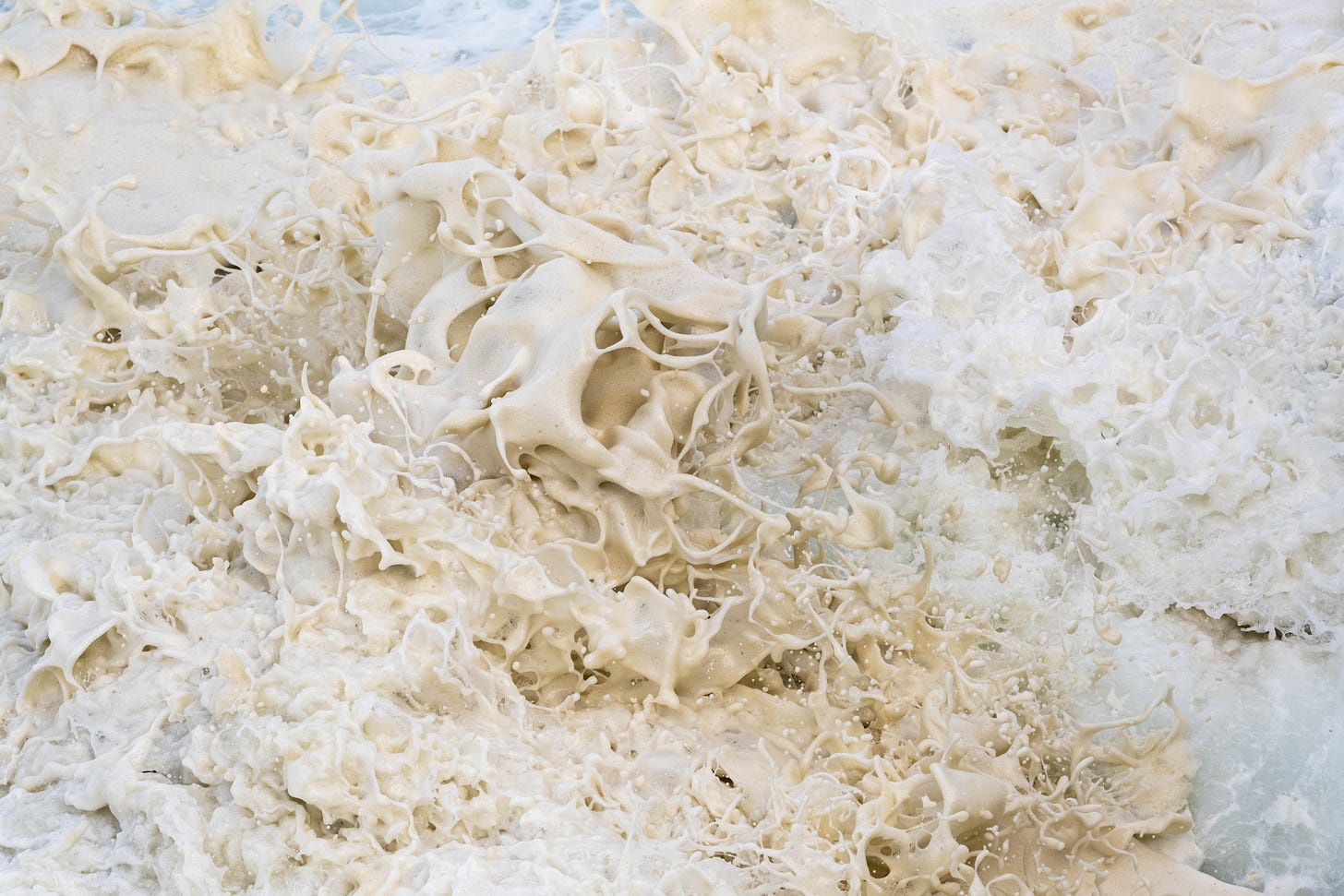

Good morning, Raymond. It's really nice to speak to you today! One image of yours that I saw recently that really struck me, was a photograph that you'd taken of something very commonplace here in Orkney, a churned up foamy breaker near the shore. And you’d taken it with this incredibly fast shutter speed. I was so struck by it, because it completely transformed something that we see every day here, just by the way the camera can freeze a moment.

It got me thinking about how photography has this capability of showing us things that we wouldn't normally see, because of the way that it freezes time. I wondered if that was something that you thought about when you're working with wildlife photography?

Image Credit: © Raymond Beasant, Westray Spume

Raymond Besant: Yeah, it's interesting, because I was a photographer first, and then got into filmmaking. So, I have this constant battle when I see something about whether I'd like to be filming it or photographing it, or vice versa. For the vast majority of the time, when I'm filming wildlife, I'm slowing it down, just to allow you to see what's actually happening. Everything happens so fast, so if I record something at the speed we would see with our own eyes, it looks really fast. Maybe we’ve just been conditioned to wildlife programmes when everything is slowed down. So it has a very practical level. But then a more creative side comes in, in choosing how slow you want it to be.

Not everything lends itself to high-speed filming. An elephant, for example, doesn't do that much, really. So if you slow down too much it becomes unusable. A lot of the time I'm filming for an editor, so I'm constantly thinking about ‘how can I film this in such a way that my editor has something to work with?’ So, for instance, to get that wave picture you mention, I'd have to go down to maybe 100 frames a second, whereas if I filmed an elephant at 100 frames a second an editor would absolutely hate me for it!

In terms of that picture, I'd actually gone to try and photograph something else, puffins. But there was nothing there. So it's then a case of what's there that's interesting that I could photograph? It was slightly fortuitous, because it was so windy that I was sheltering and then just lifted the camera up just enough to see over the cliff and just fired away like mad in the hopes that I’d get something that was good!

Again, it's slight conflict for me, what I'm shooting for. Are you just doing something for the sake of it, so you can put it on social media to get a little bit of back patting? More likes or whatever? I'm thinking about that this morning, actually, about why we want to stand out. Social media is a very noisy place. You're just bombarded. And that's how we see a lot of imagery, especially photography now.

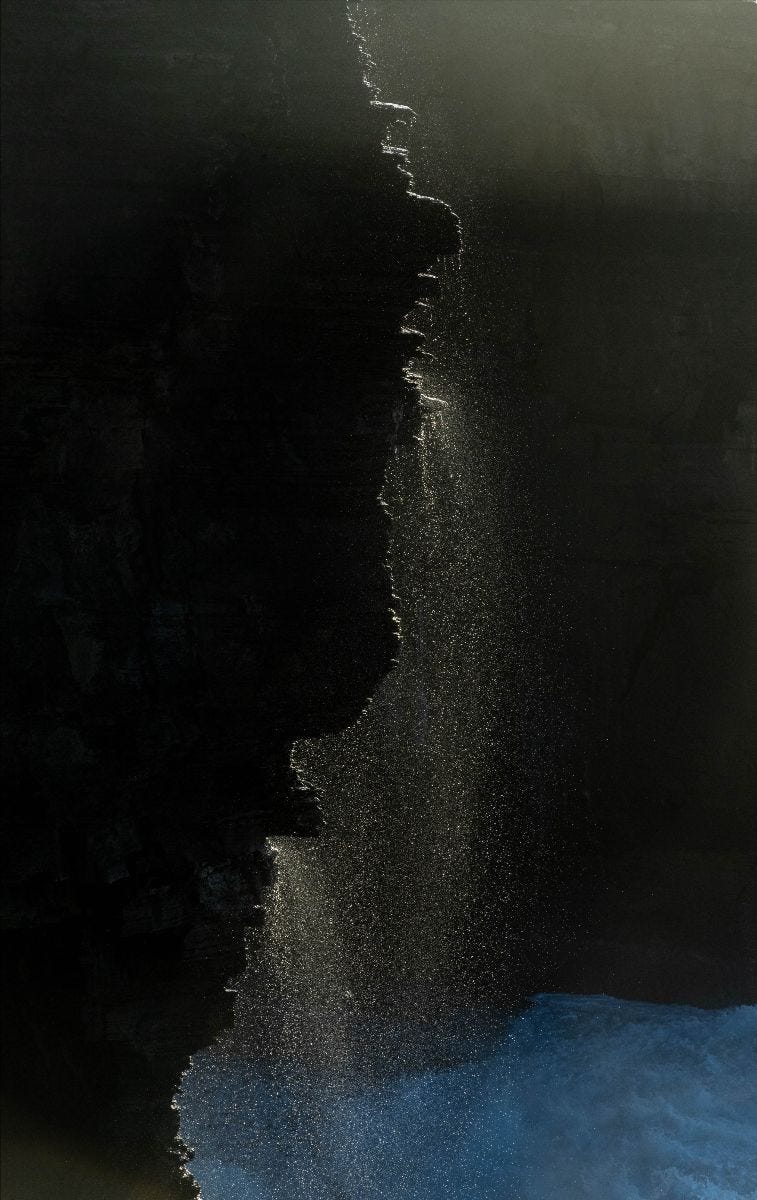

Image Credit: © Raymond Beasant, Yesnaby Smoke

Really, I'm thinking about light the whole time…

SC: It seems like there's something very different going on when you're shooting for a film editor who has a story that they want to tell. You're making decisions about how to help them tell that particular story. But then when you're out gathering material and maybe what you planned doesn't turn out, that offers you a chance to be more creative? That there's a different thing going on when you're just working for your own agenda?

RB: Yes, for filmmaking I get employed to film behavioural sequences, so you're trying to tell a story of some sort from an animal's behaviour. A lot of the time I use a massive zoom lens, often very far away. And for filmmaking the big thing, compared to photography, is light. There's a reason that you film at the beginning of the day and end of the day if you can, because the light’s softer, better for textures and detail and to create an atmosphere. And on a practical level the kit I use is so heavy and bulky. So in that sense, sometimes you're limited to what's in front of you.

With photography you’ve just got a camera in your hand. It's easier to be to move around. I think it’s something I've probably been quite good at, that If I go with the intention of photographing something, and it doesn't work, I've always been able to see an opportunity somewhere. It’s often brought about by the conditions at the time, so bad weather or good weather are something fortuitous.

But I do try to plan. It comes from experience, knowing if I go to a certain place, where the light is going to be there at a certain time of day. Really, I'm thinking about light the whole time.

For me, it's always been more about observing wildlife than filming wildlife

SC: It must ask an enormous level of patience and persistence, the work that you do. When you talk about experience, that experience must also be the observing wildlife, knowing when and where you're likely to see particular behaviours, and waiting for that.

RB: When I’m asked to film, usually lots of research has already gone into the shooting before you even go, because they want to give themselves the best opportunity for you to get the footage.

Image Credit: © Raymond Besant, Sanday Curlews

But there are long periods of time where you just don't see anything, and then the challenge is staying focused enough to be able to then record and film when something does happen. Because if you're if you're sitting in a hide that's hot, you will fall asleep! I think there's this kind of myth that you're just super on it the whole time. But it's just physiology. Everybody gets tired. And you get bored.

But for me, it's always been more about observing wildlife than filming wildlife or photographing it. My interest in photography developed from an interest in the natural world. So I'm always very mindful of how to approach animals, birds and animals. Because, if I don't do it properly, I just won't get the footage.

So a lot of time goes into field craft, and I might not necessarily film an animal at first. you It’s temptation, I think, if you've been waiting a long time, and then some something suddenly turns up, just to film it straightaway. But that animal might have taken a long time to get there because it's wary. Even a movement of your lens in a hide might be enough to scare something off. So sometimes it's about knowing when to film.

And I often think it's actually knowing when to stop as well. I film otters a lot, mostly in Shetland. There's an animal that's got amazing senses. You're in a battle of wits with this animal that can smell you a mile off. I've had some very good sessions where I've managed to be with a family of otters for, like, seven hours in a day, when they don't know you're there. That's rare though. But I really want to leave a situation if I've been filming or photographing, without disturbing it at all. I think there's a kind of disconnect I see, in social media that’s not deliberate, but a kind of a lack of…respect is probably not the right word.

There’s a difference between looking and seeing.

SC: It's almost like courtesy. What you're talking about sounds like courtesy, that you're allowing the animal to approach you and get comfortable. And that you're not pushing too far, trying not to make it uncomfortable.

RB: Yeah. It sounds quite cheesy, but I often say ‘Thank you’ after I’ve finished. Or I'll say something like, ‘Alright. Brilliant. See you tomorrow!’ or something like that.

Image Credit: © Raymond Besant, Selkie

I think there’s a difference between looking and seeing. It's easy to get caught up in the camera side of things and the technical side of things. I remember when I first started, the very first time I went to film otters in Shetland, the guy who was showing me around warned me, you're gonna get ‘blood in your nostrils’. And that's when you need to stop. Just in terms of like, well, I've got these shots getting closer and closer and closer. It's important to really respect to the creatures that you're trying to film or photograph.

SC: And it's perhaps not always the case, like you say, with social media and the popularity of taking shots of wildlife and posting them. People can become quite acquisitive about getting that shot, and then getting the likes when they post it.

RB: Yeah, I think I probably was guilty that myself to begin with. But it comes back to that responsibility. I'm sure 99% of people that photograph wildlife do it because they really enjoy it and they hope to learn something. But I think the danger is that it can bring pressure on certain sites and certain animals. You see that in certain places is Scotland that are popular. There's definitely pressure on some animals. I think it's just about being slightly savvy. There's no to need to tell everybody everything. I’m quite happy to put down the camera if I'm just enjoying something, like if I’m on a cliff and there’s fulmars flying past or something, I can definitely just put the camera down and just enjoy, watch them being good at what they're doing and I’m fine with that.

Missing the moment

SC: So the camera can be a tool to help us see something, but then when it starts to become about getting the right shot it can then become an obstacle to just being in that moment and observing that animal or that place and just actually being there?

RB: Yeah, there's definitely a danger of missing the moment and I don't mean just in photographic terms. I definitely battle that. I tend to try and work on projects rather than just go out and photograph something for the sake of it. But then, If I do see something when I'm out just with the dog I think ‘that would have made a really good image!’ But I just have to accept that you can’t always get what you want.

Image credit: © Raymond Besant, Spume Selkie

SC: I wanted to talk about your books as well, first ‘Naturally Orkney’ and then the ‘Naturally Orkney: Coastline’ book, which was the second one that you did. D’you want to tell us a little bit about that?

RB: The first book was when I’d just moved back to Orkney. When I left university I became a freelance photographer, after doing a science degree which I didn't really enjoy, and I just went straight into press work. At that time, I was more interested in people really than wildlife. What's funny is how things come full circle, because during my teenage years I was very much into bird watching wildlife, with a little bit of photography. And then kind of got into like reportage and journalistic work, and I ended up being a press photographer at the Press and Journal. And I felt kind of guilty that I had lost my interest in wildlife.

So when I moved back home it felt like a really good opportunity to renew that interest properly. In some ways, the first book was just a nice project for me to learn about wildlife and botany again. And I really, really loved it. And the second book was a closer look at the coast, because that was what I always loved most about Orkney. I just gravitate towards the coast rather than inland. The coastline book allowed me to get back in the water, do more diving.

Image Credit: © Raymond Besant, Birsay Jellyfish

Orkney’s underwater meadows

SC: What about any other projects you've got coming up?

RB: I’m just finishing up some shots of the Shetland otters and that's finished. Then I've two more filming projects this year. One’s in Orkney filming arctic skuas. And then I'm going back to Gabon in September to film forest elephants again. Between that I'm going to be I'm working on a documentary about seagrass meadows.

I wanted to kind of get involved in something that was topical, but something that people didn't necessarily know about. Seagrass is getting a lot of airtime at the moment because of its kind of amazing CV in terms of climate mitigation and rewilding, all those things.

In terms of seabed coverage globally, it's absolutely tiny. It's like 0.1%, or something, or even 0.01%. But in terms of carbon capture really punches above its weight. It stores the carbon in the sediments below rather than in the fronds itself, and kind of binds the seabed. But it's something that's been really badly damaged, not just in the UK but globally. It suffers from coastal development and agricultural runoff, and just physical things like dropping anchor on it.

Orkney is really fortunate that it's got probably the best seagrass meadows in the UK, so there are quite a few projects on the go at the moment. We're trying to establish where all the seagrass beds are, so it can then be protected hopefully. But Orkney’s seagrass is also being used as a seed bank to restore other parts of parts of the UK.

Image Credit: © Raymond Besant, Yesnaby Sea

So my plan really, is just to show how beautiful it is, and what's living in it. It can be quite a slow burn that kind of message. But in some ways, I think that's as important as the kind of shock value of more concern about what's happening to the sea. We want to protect something, but…there's always there's always a but at the end of that sentence. We see it at the moment with the controversy over the Highly Protected Marine Areas that's been met with quite a vehement kind of firewall.

Certainly in the short term, conserving or protecting something means sacrificing something else. And that might mean restriction to an area that then means restriction on incomes. It all just gets so complicated. But I think anything positive imagery-wise, can get people even just talking, that’s the main thing really. There's a discussion to be had.

SC: Yes, because actually most of us don't see underwater on a regular basis , so it's very easy to forget or just not even know what's there, not know that it's been lost, and that it's valuable. So, do you see in some ways your role can be to show people and raise awareness, that there is an educational aspect to what you do?

RB: Yes, absolutely. I’d see that as my main role now. If you see a forest being cut down you can see it happening. Whether you do anything about it is debatable, but the vast majority of people wouldn’t see or know what lives under the water. As a kid, sailing in dinghies, I was always more interested in what might live under that water than what was on the surface, but in terms of education or conservation I think underwater photography a vitally important part of educating people as to what’s under the water, what threats they might face, why we should be concerned with what’s happening under the water. There’s no other way to engage people, so it’s really important.

Image Credit: © Raymond Besant, Borwick

Work on building a body of work rather try to create a sensation on social media.

SC: What would your advice be to those who are interested in doing wildlife photography, either for leisure or professionally?

RB: If you’re just out photographing and enjoying it that’s as good as anything, and if you want to improve your technique it’s just a case of practice, and educating yourself about the wildlife, rather than just photographing it for the sake of it.

But if you want to be a professional photographer, the vast majority of my income is from filming, not photography. But it goes back to what I was saying about standing out. Everyone has access to the technology so everyone can be good now. But the people I get inspired by are still by people who have put in lots and lots of time into doing it. That inevitable means a lot of failure as well. I’m not sure how you’d make enough money from purely wildlife photography nowadays unless you have sponsorship from one of the top camera firms like Nikon or do other things like guiding. You need to take opportunities where they come.

My filming work allows me to do my photography work here. I’ll have maybe five filming jobs in a year, which gives me about a month between shoots and that allows me to work on projects I’m really passionate about, or I can do other things.

My favourite photographer Vincent Mounier’s advice was to ‘work on creating a body of work rather try to create a sensation on social media.’

SC: So it’s a long haul. Not that dissimilar to creating a career as an artist. It’s a long game.

RB: Yes, but when you start out it’s hard to see that! For example, I worked on Frozen Planet 2 two years ago, but of course I wanted to do that as soon as I started out, but it just doesn’t work like that! You have to work your way up and prove you can do the job.

SC: Thanks so much for your time today, Raymond.

RB: You’re welcome!

Contact Raymond for fine art prints of his photographs at raybesant@gmail.com

Follow Raymond Besant on Instagram

https://www.instagram.com/orkneymondo/?hl=en

Follow Raymond Besant on Facebook

https://www.facebook.com/raymondbesant

Follow Raymond Besant on Twitter

https://twitter.com/RaymondBesant