Hello friends

I am fortunate to live in a lovely place, the kind of place people come to on their holidays, fall in love with and dream of moving to, one day. It’s the kind of place that, as they say, ‘casts a spell on you’. Orkney.

The very name conjures something in people’s minds. Perhaps it does in yours. Big skies. Big seas. Slivers of land suspended between them; low, rounded islands that rise out of the sea like the backs of whales. Cliffs crammed with nesting seabirds. Stones of the ancestors lying around in quiet green pastures. All encircled by a wide sea horizon that makes you feel calmer just to look at it.

All of this is true. But Orkney is not set apart from the world’s many troubles and horrors and struggles, much as it might seem at first glance.

This weekend a holidaying friend had wanted to go to the Neolithic village at Skara Brae, but the arrival of several thousand passengers from a big cruise ship that same morning meant the World Heritage Site and other ‘hot spots’ would be swamped with coachloads of visitors. So I suggested we go somewhere a bit more off the tourist trail: Rerwick Head.

As we followed the single-track roads out to the far end of the Tankerness peninsula we left the busy tourist sites of West Mainland and the convoys of coaches behind us. Low-lying farmland extended out into a wide brightness of sky and sea. The long summer grasses and the flat blades of yellow flag irises shimmered in the brisk wind.

The air glittered with sea-light and bright clouds. The calls of nesting curlew, oystercatcher, redshank, and skylark rained down on us as we walked out towards the point. Tufts of candy-pink sea thrift were crammed into in every rocky crevice of the foreshore, their little pompom blooms dancing and bowing to the blue sea behind them.

There are no trees or mountains here to trouble the calm horizontals of the landscape. You could not imagine a more peaceful environment. On such a bright breezy summer day you’d think this was a place set apart from the troubles of the world.

But war has left its imprint here. All along this headland lie the remains of a Naval battery that protected the seaways leading into Scapa Flow, the largest natural harbour in the Northern Hemisphere, during the Second World War.

The crumbling concrete towers, gun emplacements and bunkers lay quietly around us, aligned as if still gazing out at the sea. But the people who built and manned these posts weren’t gazing at the sea horizon with a sense of calm, not like us, two friends here seeking relaxation on a fine Sunday afternoon. Their gaze was one of vigilance, constantly aware of the very real threat of attack by sea or air.

While news unfolds of re-armament in Europe, of the horrors in Gaza and our own governments’ terrible complicity and complacency, of military parades and troop deployments in the US, of the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, of the humanitarian catastrophe in Darfur, this quiet, wildflower-studded grassland overlooking a calm sea still bristles with concrete reminders of conflict and the marks it leaves behind.

To deal with landscape as a creative artist, whether that’s in writing or painting or poetry, is to be inevitably, indelibly tangled with complex and troubling questions. To observe any landscape with care and attention is to know it is under threat. To celebrate its beauty is also to acknowledge its fragility. To delight in its widlife is also to acknowledge its dwindling. To recognise its uniqueness is also to see its connectedness, its entanglement with other places.

Aldo Leopold addressed this grief when he writes in “A Sand County Almanac”: “One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives…in a world of wounds.” A historical and political education surely has a similar effect.

How, then, to respond creatively to this and not become overwhelmed with grief, or feel guilt that any pleasure and peace we enjoy is a privilege?

In his wonderful essay collection “Inciting Joy” Ross Gay understands both the intimate relationship between grief and joy, and the freedom and lightness that joy brings. Joy is a feeling that Gay describes "as thousands of birds taking flight in my chest, which means, I think, the long and beautiful breaking into something more than me." He explores this from multiple angles, but most of all through the experience of the death of his father, which he writes of with compassion and insight.

This is no simplistic call to ‘find your bliss.’ This joy is complex. Gay is unafraid of the darkness, loss, injustice, grief and anger that are part of our experience, but he also flatly refuses to accept that the joys we do find are a privilege. They are our birthright.

Gay also turns to community, connection and care and as incitements to a joy that is necessary to our shared survival. He understands joy as an act of resistance against injustice, as insurgency against conformity, as a refusal of so-called rugged individualism and a deep recognition that we live "in dependency", each of us beneficiaries of "a largesse so large and so deep you will never in one lifetime get to the bottom of it".

When I return to my studio, and attempt respond to my place and time in painting, I carry these thoughts with me: Joy and grief don’t cancel each other out. You can, and must, hold space for both of them.

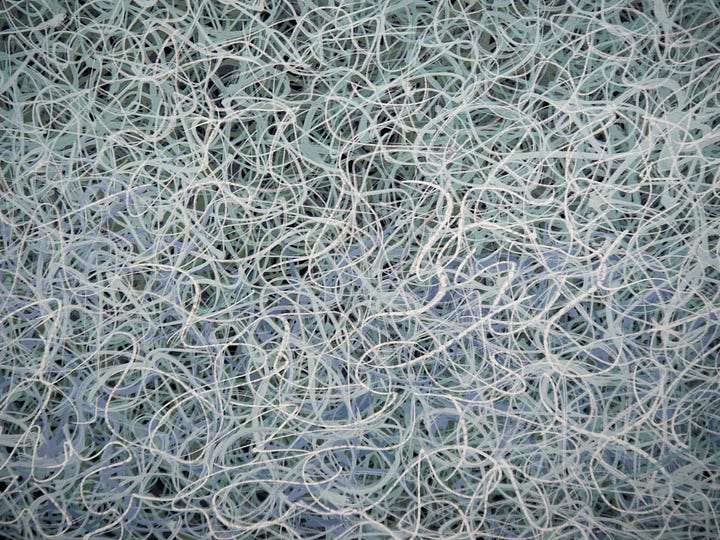

When I make paintings that respond to the exuberance of this landscape, its whirling air and water, the dance of it all, the trembling energies that run through it, the brightness, the delight, it doesn’t mean obliviousness to the darkness, loss and horror. I am choosing where to place my attention, what to give my energy to, what I want to bring more of into the world. It’s a deliberate choice, to focus on the slant of sealight peeping through, even as darkness surrounds it.

As we made our way back to the car, past a disintegrating slab that had once been the floor of a wartime building, my friend found an oystercatcher egg, laid, as is their habit, right on top of the crumbling concrete. The parents piped their loud alarm calls and we moved away to let them resume incubating this tender new life.

The Life Raft Co-Creating Community

If you would like to incubuate your own creative work, join our weekly creative co-working session on Zoom. It’s very simple. We just say hello at the start and say what we plan to work on and then leave our cameras on and work together in companionable silence. We start at 3pm UK time and finish around 4.30pm. Just click the link below to join us.

That’s all for this week!

Sam

.

The puffin numbers were down but the gannets have recovered from avian flu and were in abundance, as were the guillemots and razorbills. The gannets that had recovered from avian flu have black eyes instead of blue. Nature's works are extraordinary.

Sam, you write as well as you paint. The WW2 gun batteries you described reminded me of my visit to Bempton Cliffs at Bridlington this last weekend to see the thousands of nesting seabirds at this special RSPB reserve - puffins, gannets, guillemots, fulmars and kittiwakes. As my son and grandson approached the reserve we saw perched on a headland crumbling gun emplacements, a reminder of the past and our uncertain future. The irony did not escape us that this wild North Sea cliff face once had a more deadly purpose.