Last week I ventured forth from my quiet island home in Orkney and made a rare expedition to the Bright Lights of the Big City, to spend a few days in London. Mostly we were visiting old friends, but I also took the chance to recharge my art batteries by seeing some exhibitions.

London is awash with great art. The main challenge is not trying to see so much you become overwhelmed. But I always love going to Tate Modern. One of the things I like about it is that you can pace yourself by relaxing on one of the squashy leather sofas by the escalators, where I confess to having had the occasional restorative catnap between art-viewing. You can take your time, make a day of it.

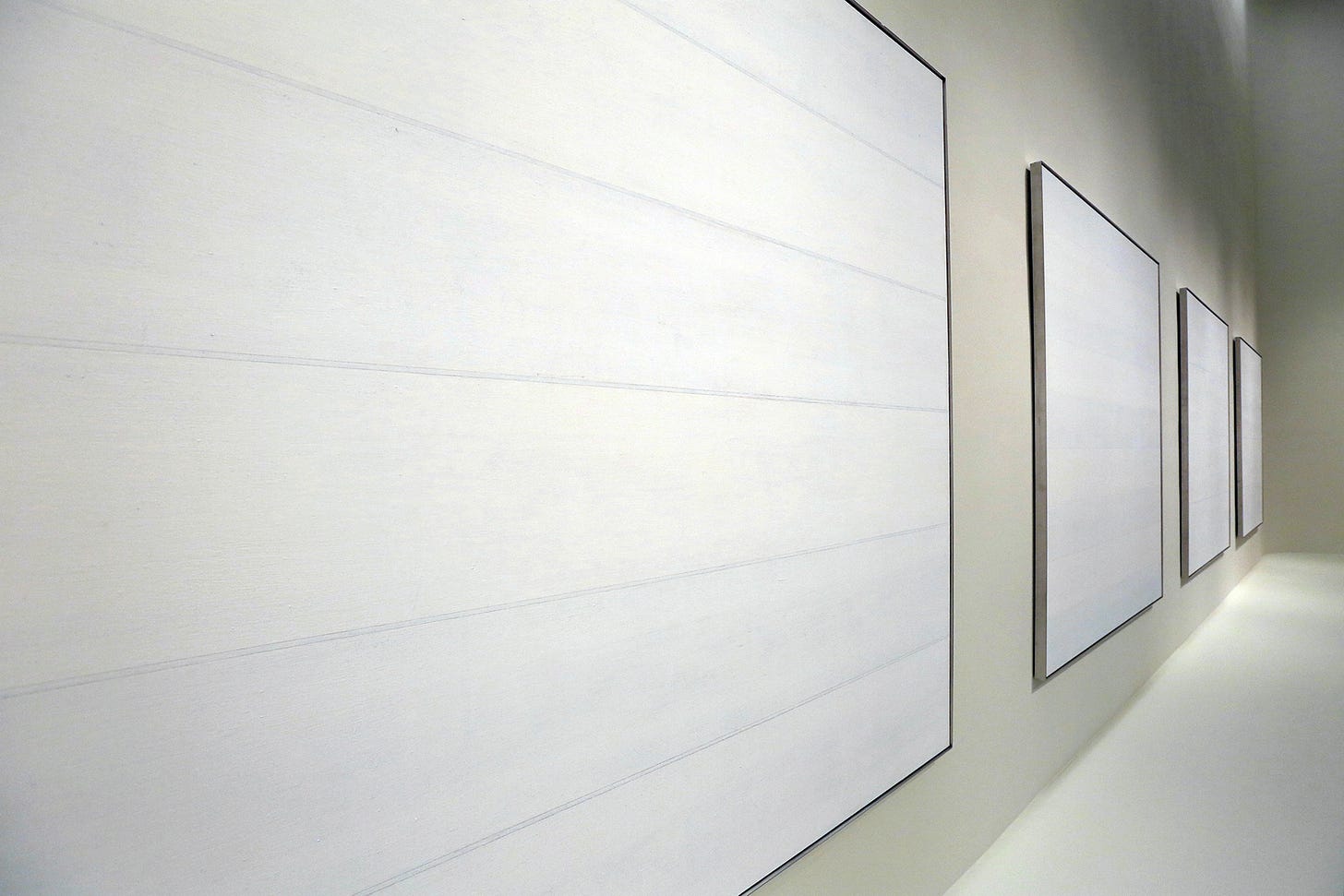

Back in 2015 I went to see a major retrospective of the artist Agnes Martin’s work in this same gallery, and was so moved by seeing her exquisitely subtle ‘Islands I-XII’ series in the flesh that I spent a whole afternoon that room, just taking them all in slowly. I ended up writing about the experience in my book The Clearing:

Sitting on the low bench in the middle of the room, I consult each painting in turn, giving each one my full attention. I lose all track of time. Everything else falls away. These are plain paintings, even by Martin’s standards, square and white, with subtle bands of palest grey underpainting, and an air of absolute silence.

A square is content. It doesn’t need anything. It rests within itself. Each painting in here is as plain as a nun. They are still and contained, and yet seem to hum with energy, as if Martin has found a way to paint light and formlessness, to paint attention balanced on the head of a pin, to paint the open, luminous space of the stilled mind. She was right about the square, the grid, yes, you can go in there and rest.

This time around, I’d gone to see the retrospective of another great painter, Philip Guston, which is definitely worth seeing (and I’ll write about it another time). But it was the installation in the Turbine Hall by the Ghanaian artist El Anatsui that has really lingered with me.

As you enter the building you’re at first struck by the sheer spectacle and scale of the installation. It takes real bravura for any artwork to hold its own in this vast hanger-like turbine hall. Anatsui’s works are suspended from the ceiling, emphasising the full height of the cavernous space. They appear, puzzlingly, at once heavy and diaphanous, weighty and sheer. It takes a while to work out what you're really seeing here.

At the back of the hall, ‘Act III, The Red Wall’ resembles a solemn, towering black sail, as if from huge ghost ship, a reminder that the Tate fortune was first made from sugar cane and the transatlantic slave trade that shipped 12.5 million Africans to the so-called New World to cultivate it. Or perhaps what we are seeing here is a wave of detritus lapping a concrete shore, a comment on the excess, consumption and waste of our current economic system.

Because as you look closer you begin to see that the whole thing has been made from recycled liquor bottle tops and other fragments that have been meticulously cut, folded and fixed together with copper wire. Walk around the back and the whole thing starts to gleam with a golden lustre, turning garbage into beauty, and the true detail of its making starts to become clear.

As

wrote about her own experience of this work in The Gallery Companion:The artwork tricks you in lots of ways. From a distance the curtain looks like soft, sheer, weightless fabric, but as you get closer you realise it’s made of bits of metal rubbish all held together by thin wires; imagining the weight of it is mind-boggling. And then there’s the patchwork of many colours that look uniform from a distance. I could spend hours looking at it. You start to think about how long it must have taken to make, how many hands, how much labour went into its construction.

As I commented on Victoria’s post, part of what drew me to this work is the sheer density of time it holds, the thousands and thousands of hours of painstaking work contained in its making. Somehow that gives this work a kind of presence. It's as if it inhabits time differently and invites us to do the same.

Art can hold time, slow time down, allowing a moment to dilate with meaning and connections, and as we experience this we come to realise that each single moment doesn't just have duration, it also has the potential for depth, for amplitude, for layers and ramifications.

A 16th century moment caught in time

Nearly 20 years ago, the art critic Robert Hughes made a plea for ‘slow art’.

We have had a gutful of fast art and fast food. What we need more of is slow art: art that holds time as a vase holds water: art that grows out of modes of perception and whose skill and doggedness make you think and feel; art that isn't merely sensational, that doesn't get its message across in 10 seconds, that isn't falsely iconic, that hooks onto something deep-running in our natures.

Another exhibition that I visited the following day also captured and slowed time, albeit in a very different way. Holbein at the Tudor Court at the Queen’s Gallery shows us the sketches and drawings Hans Holbein made, often in preparation for his breathtakingly lifelike portraits. The drawings are as soft as breath, exquisitely delicate, and yet bring to vivid life the people of the 16th Century around the court of Henry VIII.

Something about the apparent simplicity of drawing, its modesty of means, makes us aware of the artist’s hand and its careful movements, perhaps the exchange of quiet conversation between sitter and artist in the shared moment of the sitting, a moment from hundreds of years ago caught, as if in amber, and held on the paper.

The audio guide invites visitors to explore ‘slow looking’ by following a specific line or detail and lingering with it. This did cause a bit of congestion in such a busy show, but I enjoyed the permission to linger over the details of eyelashes, pearls, lace.

The intimacy and psychological insight of Holbein’s drawings is startling. However, this exhibition doesn’t offer an overview of his work. There are only a few of his finished portrait paintings here, but those that are included stop you in your tracks. These are human beings, as vivid and complex as you or I. His portrait of a cold-eyed Thomas Howard, uncle of Anne Boleyn, is absolutely chilling. You wouldn’t like to cross this man, would you?

If, like me, you are planning to join

on his year-long slow read of Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall Cromwell trilogy, which he has memorably called Wolf Crawl, I can recommend a visit to this exhibition to get you in the mood!In my studio this week

Back in my own studio, things are progressing…slowly, appropriately enough, although my efforts are indeed paltry compared to the art I saw last week. Before I set off for London, I had begun a new larger panel, first covering the whole thing with aluminium leaf to lend a subtle lustre beneath the paint.

Since then I’ve been laying down washes of paint and letting them evaporate. They take a long time to dry in the winter, so it’s taking a while to build up the surface I want to work on. A few more layers to go, I think, before I can start on the drawing proper.

But I’m pleased with how the two smaller pieces I’m working on are shaping up. This one’s nearly done…

And this pale one has a little bit still to go…(If you have the sound up you’ll hear that I’m drawing while listening to Handel’s Messiah, to help drill the music into my brain for a choral performance I’ll be taking part in soon!)

I have several exhibitions lined up for 2025 so next year I’m going to have to hold on to quite a bit of work for those, but I will be releasing these two new paintings very soon. I’ll let you know the details next week.

Thank you so much to those of you who have opted for a paid subscription. I really appreciate that you value my work and wish to help support it even though I have no paywall. As a thank you to my paid subscribers and anyone upgrading to a yearly subscription before Sunday 26th November I’ll be offering a 20% discount on the new artworks I’m releasing next week.

wishing you a slow week

Sam

So enjoyed reading this, and seeing your beautiful photographs. I first encountered El Anatsui’s work in an exhibition in Abu Dhabi in 2012, he’s been one of my favourite artists ever since, his concepts are breathtaking in their apparent simplicity, and full of symbolism. I’m hoping I can make it to the Tate before it finishes. The Holbein’s I have been lucky enough to see, they are very special. Looking forward to following the journey of your latest work, it already looks fabulous, love aluminium leaf.

Oh, I need some more slow in my life right now, Sam. An enforced slowing! Your work is mesmerising, as are these lovely videos of you producing them. Can't wait to hear more about your exhibitions and I'll be joining you for Wolf Crawl, hot on the heels of a festive London visit... I'm building my itinerary now!