I’ve been finding it hard to sleep lately. Maybe you’ve been the same.

I’ve had to start rationing my time on Twitter, not so much because of the big black ‘X’ and other changes to the platform, but because I follow a number of climate scientists. They are, frankly and openly, terrified at what they are seeing in the data. I don’t think I need to spell it out. We’ve all seen the graphs and the pictures.

They thought we had more time. We all thought we had more time.

We are being told to be extremely scared. And at 4am, I often am.

But I’m not sure it’s all that useful to this beleaguered planet, to be bleary all day from the sleeplessness of climate dread. I’m trying to focus on longer form written journalism that doesn’t just throw terror and apocalypse at you then cut to celebrity gossip and adverts for fancy cars, but tries to make some sense of things. And I am looking to learn from wiser minds, writers who have thought long and carefully about our predicament. Books, as always, are my friends and teachers.

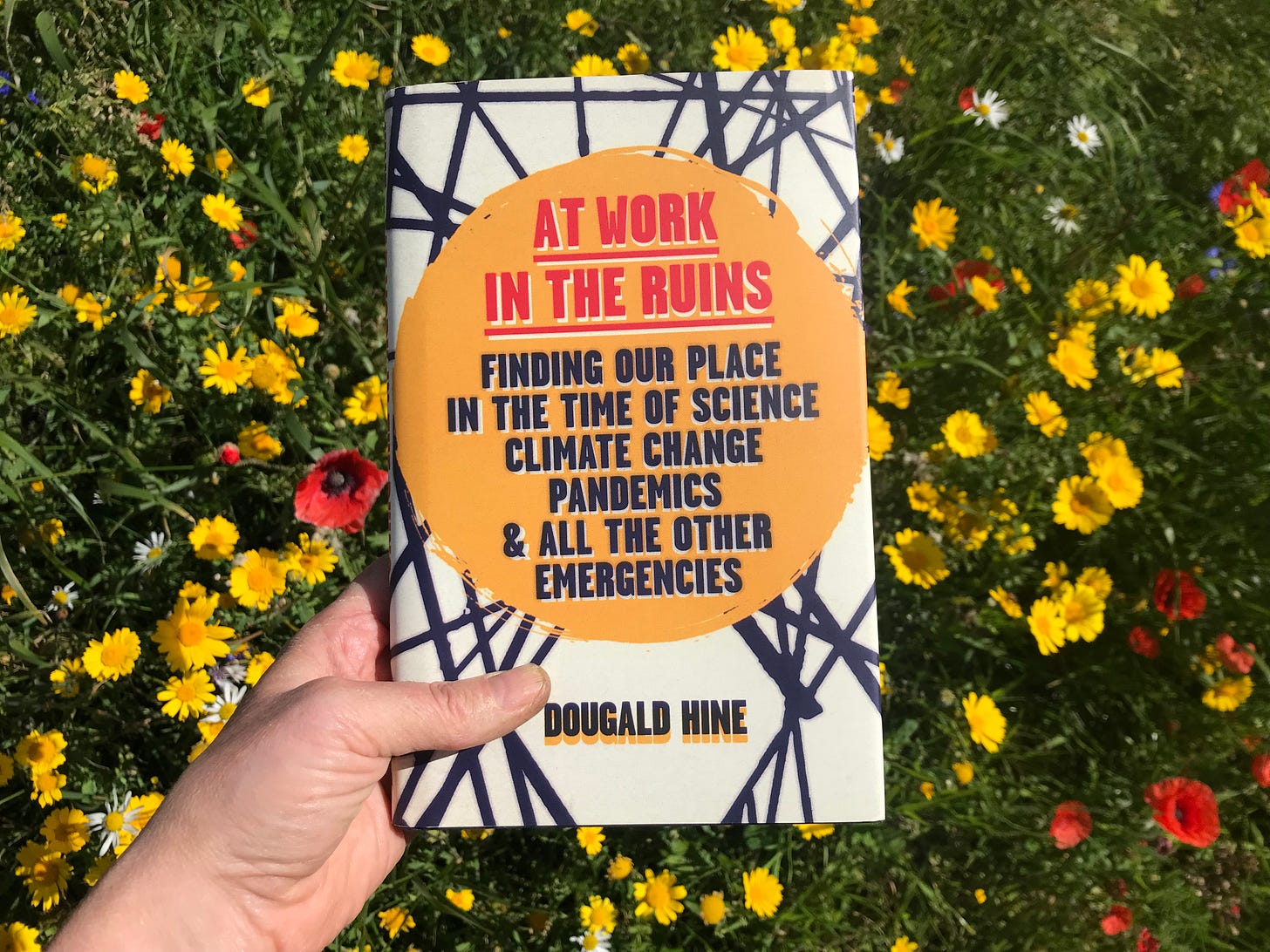

Dugald Hine’s ‘At Work in the Ruins: Finding our place in the time of science, climate change, pandemics and all the other emergencies' is one such book. Hine doesn’t look away from the pile-up of calamities, but when I read his words “I reserve the right to be less scared than I’m told I should be” in the prologue, I found myself inclined to read on, grasping for straws of hope or consolation.

Hine doesn’t pretend that things will be OK. Anything but. “Something is coming over the horizon, a humbling from which none of us will be spared, that will not be managed or controlled, but will leave us changed.”

But he warns against nihilism:

“The end of the world as we know it is not the end of the world full stop. Unless we can inhabit that distinction we will end up defending the world as we have known it at all costs, no matter how monstrous those costs turn out to be.”

There are no certainties here, not even bleak ones.

Hine describes how we all need to hit that ‘oh fuck’ moment, when the seriousness of our predicament becomes clear to us. I can remember my own ‘oh fuck’ moment. Perhaps you can too. Mine came, seemingly out of nowhere, a number of years ago. Early one morning I awoke in the quiet calm of my little white bedroom with a sudden felt sense of the sheer enormity of what was happening to the planet. It was as if I could actually feel entire icecaps melting at both ends of the earth as I lay there in my little bed, in my quiet little room, the waves of dread washing through me and not a clue what to do but to go on recycling my plastics and creep about switching things off, all the time feeling the ridiculous mismatch between the vast, systemic scale of the problem and the tiny, individual scale of the solutions we’re offered: change to low energy lightbulbs, switch off standby, use a shopping bag. I did all these things, and still do, diligently, out of habit now, all the time feeling like I’ve been duped.

Panic can’t last. It burns itself out. Since then, I’ve been puzzled sometimes, at the numbness that comes over, how I can scroll past those terrifying graphs, the clips of burning forests, red skies, brown torrents, hailstones like rocks, and after some metaphorical hand-wringing, turn back to my day and go on with my allotted tasks, quietly hoping that my privilege will protect me just a bit longer, that it will be a little while more before the fires and floods will reach us here.

Hine recognises this weird blankness when he writes:

“The trouble we’re in is deeper than I know how to talk about. It’s deeper than I know how to feel.”

The trouble we are in, Hine suggests, is not a problem. Rather, it is a predicament. This distinction is an important one. A problem has a solution. A predicament, he points out, “offers courses of action, but none of them is a solution.” Again, we have no certainties, and no solutions.

We may not be able to fix this thing, but that doesn’t mean we just lay down and give up.

Hine advocates for training our attention on the real people and places around us.

“We will need to rediscover that any world worth living for centres not on the vast systems we built to secure the future, but on those encounters that are proportioned to the kind of creatures we are, the places we meet, the acts of friendship and the acts of hospitality in which we offer shelter and kindness to the stranger at the door.”

Meantime, here’s some wildflowers I sowed this spring.

Small actions then, are not impotent but serve to ground us in our own lived realties, and not those we only encounter through screens, statistics and graphs.

“A growing number of people are having an encounter with climate change not as a problem that could be solved or managed, made to go away or reconciled with some existing arc of progress, but as a dark knowledge that calls our path into question, that starts to burn away the stories we were told and the trajectories our lives were meant to follow, the entitlements we were brought up to believe we had, and our assumptions about the shape of history”

Hine finds hope, not in technological or engineering breakthroughs that approach our predicament as if reducing carbon emissions were the only thing that mattered. While he thinks the technofix approach will likely gather momentum as governments find it increasingly hard to ignore climate catastrophe, it’s a vision of the future that’s dependent on yet-to-be-invented technologies. He sees hope in activity much closer to the ground, at much smaller scales, not the “Big Path” that we might read about in the news, but the “Small Path”. Lots of them.

“The political orthodoxy…sets out to limit the damage of climate change through large scale efforts of management, control, surveillance and innovation, oriented to sustaining a version of existing trajectories of technological progress, economic growth and development. The small path is a train that branches off into many paths. It is made by those who seek to build resilience closer to the ground, nurturing capacities and relationships, oriented to a future in which existing trajectories of technological progress, economic growth and development will not be sustained, but where the possibility of a ‘world worth living for’ nonetheless remains. Humble as it looks, as your eyes adjust, you may recognise just how may feet have walked this way and how many continue to do so, even now.”

Hine considers that the path to the future is a patchwork of many small paths that together form a countermovement to the Big Projects of power:

“Opposing trajectories can be playing out at the same time, operating on different scales. When I speak of the Big Path and the small path, they coexist for a good while yet, the one at the centre and the other closer to the edges. There is no straight contest of power here, nor even an agreement over that is at stake, and the significance of the events we are part of will only be apparent in hindsight. So, the seeming imbalance in the strength of the opposed forces may not be all that it appears. This is a thin strand of hope, I grant you.”

Thin strand or not, I’ll take it.

Hines warns:

“We are not entitled to a happy ending, or even to know more of the story than the small part any of us gets to play. But too many of us have been told the story is already over, that there is nothing left to play for, and this is a lie. “

There are no solutions to our predicament. There are only courses of action.

The story is not over. We don’t know how it ends and won’t get to find out. Our part of it is only ever a small one.

The path to the future is one that is made by walking, and it may look more humble than you think.

I’m so glad I paged back to read Hine’s thoughts and your processing of same. I experience you as a source for right thinking. Quite difficult to encounter on most social media. Thanks, Samantha

I’m glad you re-posted this Dougald Hine article too. I’ve lost all ideologies and faiths now. All the big one way and no others that got us here. And can’t even think these days without walking. But once I do walk all the imponderables unravel into separate threads and small possibilities that, yes, might just add up. And certainly save me, time after time, from ever despairing.