Where is your nearest fresh water?

For sure, it won’t be far away. We can never be very far from our next drink of water. Do you have some in a bottle, or a glass nearby? Or is it the water in your kitchen sink, or the toilet next door? Stop for a moment to think about where that water comes from? Bring to your awareness the invisible web of pipes running through the building you’re in, how these run underground to connect to a water main that’s perhaps fed by a reservoir miles away, or maybe by a borehole deep underground.

And while we’re at it, let’s contemplate for a moment the physical strangeness of water. It is the only substance that is present on Earth in all three states, solid ice, liquid water and gas as water vapour. It has the highest surface tension of any liquid apart from mercury. In conditions of zero gravity liquid water will form itself into a sphere. It has the unique property that its solid form is less dense than its liquid form, allowing ice to float. Without this, all life on the planet would have ended at the first ice age as the oceans would have frozen solid.

And how are all these reservoirs and aquifers, cisterns and taps replenished?

Rain.

So, let’s think for a moment about where our rain comes from? Here in Orkney most of our rain comes across the Atlantic on that great Atmospheric River we call the Gulf Stream and its northerly branch, the North Atlantic Drift, as the condensed water vapour of the atmosphere, scooped from the sea on prevailing winds. Rainfall is the primary source of most fresh water on the Earth. But rain doesn’t just fall and then flow straight into the nearest stream and into the reservoir. It seeps into the soil, it holds in puddles in the wet winter fields, it lingers in bogs, trickles down into aquifers. Did you know that the soil under your feet is only 50% solid? The other half is water and air. The ground is full of holes in which water pauses, and crevices through which it seeps, soaks and oozes.

And that slow seepage of water through the world includes our bodies too. Our eyeballs hold the same percentage of water as the sea. We look at the world through a lens of ocean. Water lubricates and cushions our joints, fills our mouths, cleans our eyes, cools us in sweat, flushes our waste, carries oxygen in our blood, breaks down our food. Every cell of our body is part of the water in the world. But it pauses in our bodies just for a short while before moving on. Every time we exhale we are sending invisible water as vapour back out into the world. About 400g of it a day. The same goes for animal bodies. Every cow grazing in every field, every bird, every deer, every fish, every cat and dog, is part of the world’s water.

And of course, every green plant. What holds those slender blades of grass upright is the water in every cell. It’s water that keeps those fine shoots so miraculously upright, each one performing its own Indian rope trick. Without water to fill every cell they would wilt, slump and die. But very little of the water a plant’s roots take up remains in its cells. 95% of the water a plant brings up from the soil is lost into the atmosphere through the leaves. Each green plant is precariously balanced in a delicate exchange; the plant must open its stomata to absorb the carbon dioxide it needs to build sugars, but risks dehydration as water leaks out very much faster than the plant can absorb the carbon dioxide. As water evaporates from the leaves it pulls more water up behind it to replace what is being lost, sucking it upwards from the roots, through the tubular xylem in the stem, out to every leaf and then into the air, the water cycling through a single soil-plant-atmosphere-continuum. Green vegetation creates clouds and can generate rainfall, creating local microclimates. Clouds then, are born in the ground.

Spread out in every field and garden around us, a billion slow, green fountains are sending water invisibly into the air. If only we could see it! A diamond-mist of water vapour, sparkling upward and drifting over the land in great sheets.

This world of ours is a world ‘Wetness’. The visible water we see is only one aspect of the diffuse presence of this element in the world. 'Wetness' is water as breath condensed on a misted window on a chilly morning, or hanging, like a soft ghost, in the cold night air, is water held in plant, flesh, bone, soil. In our eyeballs. In our gut. We have been taught to think in terms of wet and dry, land and water, with a clear line drawn between them. When water crosses this line, we call it a flood, an incursion. This line doesn’t just separate water from land. It creates and defines them as two separate and distinct entities.

I take this understanding of water as ‘wetness’ from the work of landscape architect and planner Dilip Da Cunha. He argues that “The line that separates land from water is a choice, not in where you choose to place it, but in the fact that you draw a line at all,” He proposes that instead of a division between dry land and wet water, the real state of affairs is much more blurred:

“one has here a ubiquitous wetness of varying extents. The wetness does not flow as rivers do; instead it is held for varying extents of time ranging from seconds and minutes to centuries and eons in soils, aquifers, snowfields, tanks, building materials, agricultural fields, air, and even plants and animals...it soaks and saturates before exceeding only to be held again. This is not water draining into the sea; it is rather rain moving in complex, field-like ways."

Rain is a wetness that is everywhere before it is water somewhere. Rain doesn’t run in a river but holds in everything, air, earth, breath, every living cell, the walls in our damp cottage, and back into the sea or the atmosphere. This is not, then, a linear waterworld where rivers flow from source to sea and the edge between land and water is distinct and separates the one from the other, but “a field-like world where identities extend into one another for varying extents of time.” A world of wetness.

We often use water as a metaphor for the passage of time. The earliest clocks used water to measure time as water dripped through a hole in one earthenware vessel into another. We say that time ‘flows’ like a river, in one direction, from source to sea, birth to death. But once we start to see that really water doesn’t flow in a line but within a multidimensional moving field of wetness that extends vertically between clouds above and aquifers beneath, as much as it does horizontally in rivers and oceans, maybe this gives us another way to think about how time moves too.

In the context of the climate emergency, when we feel a growing sense of urgency, that time is running out and that the future is frightening, to think about time as a single, inexorable, unidirectional line is to become prey to fear, fatalism, and perhaps also despair and nihilism. ‘It’s too late.’

But many philosophies, and now science too, tell us that time isn’t like a pot with a hole in it. It can’t run out. Nor does it flow like a river. Time isn’t a neutral, separate, uniform dimension in which events occur. Time is, we are told, multiple and varied, affected by mass. Time at the bottom of a deep ocean trench unfolds more slowly than it does among the clouds. Reframing the ways we tend to think about time, to this more varied, embodied and diffuse web of multiple times, in an interlocking weave of causes and effects, can offer us more space for uncertainty, possibility and hope.

And perhaps we think about our lifetimes and actions in this way too, not as something discrete that begins at conception and ends in the grave, but as an intricate web of connections, causes and effects, the thousands, perhaps millions of other lives we’ve touched, the actions we’ve taken, only a few of which we will ever be aware of.

Water is a real, tangible phenomenon in our familiar, shared, everyday world, but something about its nature helps us to reach towards parts of our lived experience that are mysterious, puzzling, humbling, elusive, or just too big, complex and paradoxical to hold steady in the mind; the way a simple glass of water in our hand reaches back through taps, pipes, reservoirs, and rivers to clouds, atmospheric ‘rivers’ like the Gulf Stream and the oceans, connecting our body to every other earthly body and the body of the earth.

What, then, does it mean to even try to make this wetness, this field of connection visible when my own point of view can only ever be personal, partial, located, small, and slow? The writer Annie Dillard wrote:

“How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives. What we do with this hour, and that one, is what we are doing. A schedule defends from chaos and whim. It is a net for catching days. It is a scaffolding on which a worker can stand and labor with both hands at sections of time. A schedule is a mock-up of reason and order—willed, faked, and so brought into being; it is a peace and a haven set into the wreck of time; it is a lifeboat on which you find yourself, decades later, still living.”

How we spend our days, our minutes, our moments, is how we spend our lives. I just want to be here while it’s happening. This is behind the slow and repetitive way of drawing water that I’m using. Something accumulates. I’m aware there’s a paradox, working so slowly to record something so mutable, but the work of art serves to slow time down, slow our thoughts down, so we can take a proper look at things. Not to stop anything, but to introduce a meander, an eddy. Art helps us to see that time does not just have duration. It also has amplitude, and depth.

The art critic Robert Hughes once said, in an address to the Royal Academy, What we need more of is slow art: art that holds time as a vase holds water. Line by line, mark by mark, the drawing becomes a net for gathering up time, a scaffolding, a haven in the wreck of time. This slow immersion is a way of the gathering the attention, observing a thing, in this case water, until it gives way, and becomes a window. The classical Buddhist metaphor of the Jewel Net of Indra describes the structure of reality as a web of causes and conditions stretching out in every direction with no edge and no centre, and at every node on this web there is a clear multifaceted jewel that reflects all the other jewels in the net. We can get a sense of this interdependent, ever shifting web when we consider water, not as a thing separate from other things, but as a field of ‘wetness’ in which we, too, are fully immersed.

What we need more of is slow art: art that holds time as a vase holds water.

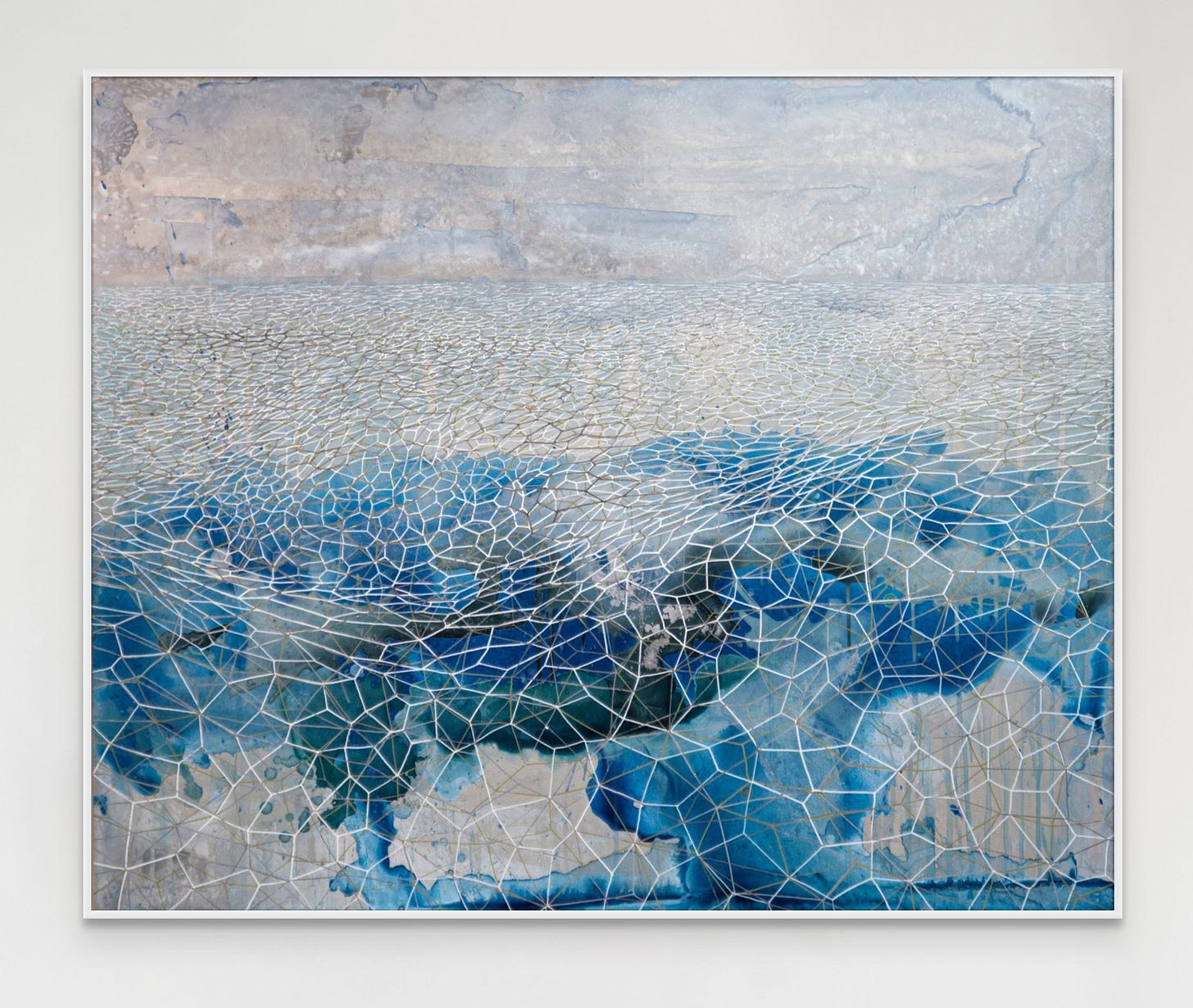

In my paintings I often use iridescent or reflective media like silver leaf and chrome ink, so the painting’s surface shifts with the changing light and your angle of vision, like water does. It’s hard to capture this in photographs. I build up layer after layer, starting with washes of colour, and then fine webs of drawing, each one over the last.

There’s always a play between surface and depth in painting. You can look at the surface, the texture, the paint itself, and see the painting as a ‘thing’. And then you can ‘flip’ your focus and look, as if through a window, into the illusion of depth created by the picture. It never settles down. It’s like when you look into a pool of water and see the ripples and play of light on the surface, and then flip your focus to see the sky behind you reflected, or maybe the rocks beneath the water.

The Canadian Poet Don Domanski captures this sense of water as a diffuse, animating presence in the landscape and the self:

it begins here I think with a raindrop

with a raindrop and a world with a cloud

and the cool morning air interlaced

with hot breath from under stones

it begins each morning with a few cloudlings

drifting toward the horizon

the horizon drifting toward

the vast spaces between elementary particles

from The Bestiary of the Raindrop

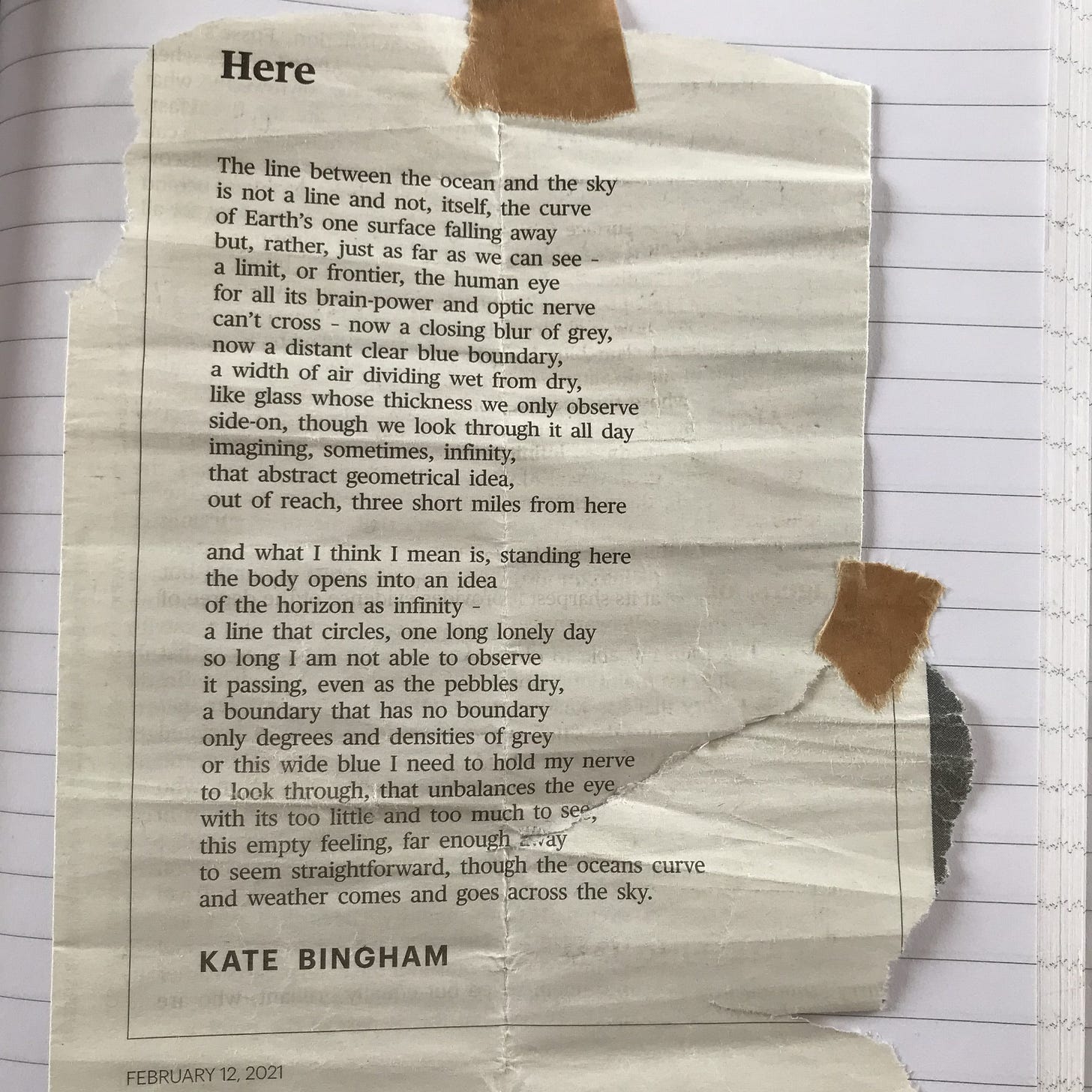

I resisted the horizon in my work for a long time. Including it felt too representative, too obvious, too ‘seascapey’. But I kept thinking about it. I kept noticing how something shifted in me whenever I looked out to the western horizon. I saw how the North Atlantic meets the sky so differently every day. I kept wondering what it is that draws our eye to it? What it is we feel when we look out to the sea horizon? Why is it that in these anxious times, when calamities seem to bear down on us one after the other with no end in sight, that simply looking out to sea can feel so rebalancing? I started to find some clues, here and there. This one appeared in the form of a poem, in the TLS I think, that I kept and folded, tucked in my pocket then lost and found, unfolded and read again, still perfect, now safely kept in my notebook.

Or, another poet, local to my patch of Orkney, Robert Rendall who wrote:

ANGLE OF VISION

But John, have you seen the world, said he,

Trains and tramcars and sixty-seaters,

Cities in lands across the sea –

Giotto’s tower and the dome of St. Peter’s?No, but I’ve seen the arc of the earth,

From the Birsay shore, like the edge of a planet,

And the lifeboat plunge through the Pentland Firth

To a cosmic tide with the men that man it.Robert Rendall (1898-1967), Orkney poet

From Shore Poems (1957). Also in The Oxford Book of Twentieth Century Verse.

Both of these poems get close to the sensation of looking into the distance towards that place on the horizon where the see-able falls away from us. For a moment, our chattering mind is confounded and silenced. Instinctively, we pause, take a few deep breaths and just gaze. It feels…good. Calming. As if something is coming back into balance. As if we are reconnecting with something still and expansive in ourselves, that gets drowned out by our internal chatter and anxiety.

When I invited people to join me in creating a big drawing as part of my exhibition at Northlight, this moment of coming back into balance seemed a common response; sometimes some resistance, a bit of anxiety about getting it wrong, and then a kind of sinking into the moment, a seductive calm within the rhythmic, repetitive movement of drawing. There is a stillness to be found here, and it’s a stillness that sits in the midst of movement, not in opposition to it.

So we’ve been thinking and reading about water, time and connectedness. But a where does a creative practice fit in to this story? In ‘On Connection’ Performance poet Kae Tempest argues that ‘immersion in creativity can bring us closer to each other and help us cultivate greater self-awareness’ and they begin with a definition of terms that is acute and bracingly crisp:

‘Creativity is the ability to feel wonder and the desire to respond to what we find startling. Or, more simply, creativity is any act of love. Any act of making.’

‘Connection is the feeling of landing in the present tense. Fully immersed in whatever occupies you, paying close attention to the details of experience. Characterised by an awareness of your minuteness in the scheme of things.’

‘Creative connection is the use of creativity to access and feel connection and get yourself and those with you…into a more connected space.’

And to create this connection, you need to pay attention to your own specific situation. Tempest writes:

‘James Joyce once told me; “In the particular is contained the universal.” I appreciated the advice. It taught me the closer attention I pay to my ‘particular’ the better chance I have of reaching you in yours.’

This closeness of attention that Tempest has developed over many years of creative practice and performance has cultivated a warmth and compassion that feels increasingly rare in these times of cultivated outrage and entrenched positions:

‘I see that every single person is affected by the violence of existence in different ways, and that people carry their burden however they can. People suffer a great deal, and ideally they must process their traumas in order to reach some kind of peace. But what if your situation is too intense and you can’t get a moment’s respite? People respond differently to things. People have different things to respond to. I am no one to judge what conclusions someone has come to. I do not want to change minds any more. I just want to connect.’

I appreciate here how Tempest dispenses with any sense of art as either self-indulgent luxury on the one hand, or on the other, polemic, lecture or activism. You don’t need to posture, shout for attention or feel self-conscious about taking up space. You don’t have to have all the answers. You don’t even need to have the right questions. You don’t need to fix the world. You just need to connect.

This, then, is what the artist (writer, composer, film-maker is seeking) not to show off, not to teach or convince or persuade or provoke or to solve or fix anything.

To connect.

To see our own particular predicament with such clarity, honesty and compassion that our reader, or viewer feels seen in their own particularity, their own predicaments and vulnerabilities.

And I would like to propose that if water is the connective tissue of the physical world, perhaps creativity can be understood as the connective tissue of the human spirit. Art is how we come to see each other more deeply, and to see and understand ourselves.

This is not a solution to the many crises we find ourselves in as the climate emergency goes on unfolding. It’s direction of travel. A course of action. In a situation as complex as the climate crisis we find ourselves in, we would do well to mistrust silver-bullet solutions we are offered. Because, as Dougald Hine has suggested, the climate emergency is not so much a problem as a predicament. And a predicament does not offer solutions, only various possible courses of action, and as our actions take place within a network of causes and conditions so much vaster than ourselves, we don’t get to see the final result. We’ll never get to find out how it all works out. Tempest advises:

‘Don’t be too hard on yourself.

You can’t be present all the time.

But the closer we focus on our experience, the greater the awareness of the experience will be, the greater the immersion, the greater the possibility for connection.’

And so we circle back, to a simple glass of water, to find it seems newly miraculous.

How big water is. How grand. How ancient. Like a god.

Water takes no shape of its own, but fills any it’s offered, enveloping any object dipped into it. From a field of wetness it gathers and falls, always seeking the lowest places. And yet it shapes our planet, eroding, weathering rocks, laying sediments, birthing life itself.

The weekend’s rain has filled the loch to brimming. The burn is bloated from yesterday’s storm, a brown and frothing brawl. Beyond, the sea horizon is ‘far enough away to seem straightforward’ though I know it’s anything but. The rock pools empty and refill with every tide. I turn the tap, fill the kitchen sink and empty it. I drink and I piss. I’m a tidal pool filling and emptying. I’m small but I touch the whole. I participate. This glass of water on my table gathers up the sunlight and pours it out again, but changed now, refracted, focussed and brightened. I don’t know what it is that slips between and around the rain dropping into the loch, the cloud passing over the sun, the water held briefly in a glass, but something bright leaks through and catches on the shimmering surface of things.

But what do I know?

Only this. That I can choose to gather up into myself whatever light there is and pour it out again, the same light I receive but changed a little, focussed, brightened and refracted.

This feels like work I can do.

The horizon gazing thing reminded me of “The Star”, tarot card that reminds us how we have to look beyond to find that reassuring calmness we need to keep going forward.

As I wake to the drops on my ceiling windows, forecast for days and days ahead, I will return again to reread your words and let my own flow into the well at the foot of the garden, flowing to the gravel bed, flowing to the Garonne under the canal, flowing to the estuary and then to the Atlantic to evaporate into that great atmospheric river again. Thank you for sharing your work in this wet wet world.