Hello friends

If you’re a long-time reader of this newsletter you may be wondering where all the nonfiction book recommendations have gone. I realise I haven’t offered any since last year. My apologies. I have a confession to make. I have been lost in fiction. Since I received Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell Trilogy for Christmas I have been living half my life in the 16th century. These three thick doorstop paperbacks, some 2007 pages of utterly absorbing, masterfully written historical fiction, have sucked me deep into the Tudor world.

I started the Wolf Crawl , a slow read-along of Mantel’s trilogy with

back at the beginning of the New Year. But I got hooked and soon found myself reading at more of a Wolf Trot, then a Wolf Gallop. I’m nearing the end of the final book now, and will surely feel bereft when I do emerge once more, with some reluctance, blinking into the bright light of the 21st century.Books take time to read, even for a fairly voracious, fast reader like me. Some deluded people, like

argue that books take too much time and it would be much more efficient for me to read a six-paragraph blog post or Wikipedia entry on the life of Thomas Cromwell. Get the job done and move on, they say.But this ignores the reality that books are time. We move through time differently in the world of a book. The dilations, contractions and inversions of time that immersion in a book offers us, where one night can last several chapters, decades pass between two paragraphs, or flashbacks dance us back and forth through a person’s lifetime, invite us to inhabit time differently from our everyday world.

A big book, one that takes a long time to read, becomes part of our lives, almost like a companion. The time we spend in its company changes us. As Joel J Miller writes in MILLER’S BOOK REVIEW 📚

A book is a tool. It’s a machine for thinking. And “all machines,” as Thoreau once said, “have their friction.” The time it takes to engage with ideas—whether factual or fictional, emotional or intellectual, accurate or inaccurate, efficient or inefficient—might strike some as a drag. But the time given to working through those ideas, adopting and adapting, developing or discarding, changes our minds, changes us.

It’s not about the wisdom we glean. It’s about what wisdom we grow.

And that growth takes time and attention. A good book takes our wayward, distractible mind and gives it one job to do. It trains us to focus. We live in a world of social media and 24-hour news cycles and we cannot, indeed should not, retreat from it entirely. But we need to find ways to be more conscious about where we choose to direct our attention. There’s an ethical, even an ecological dimension to this attention economy.

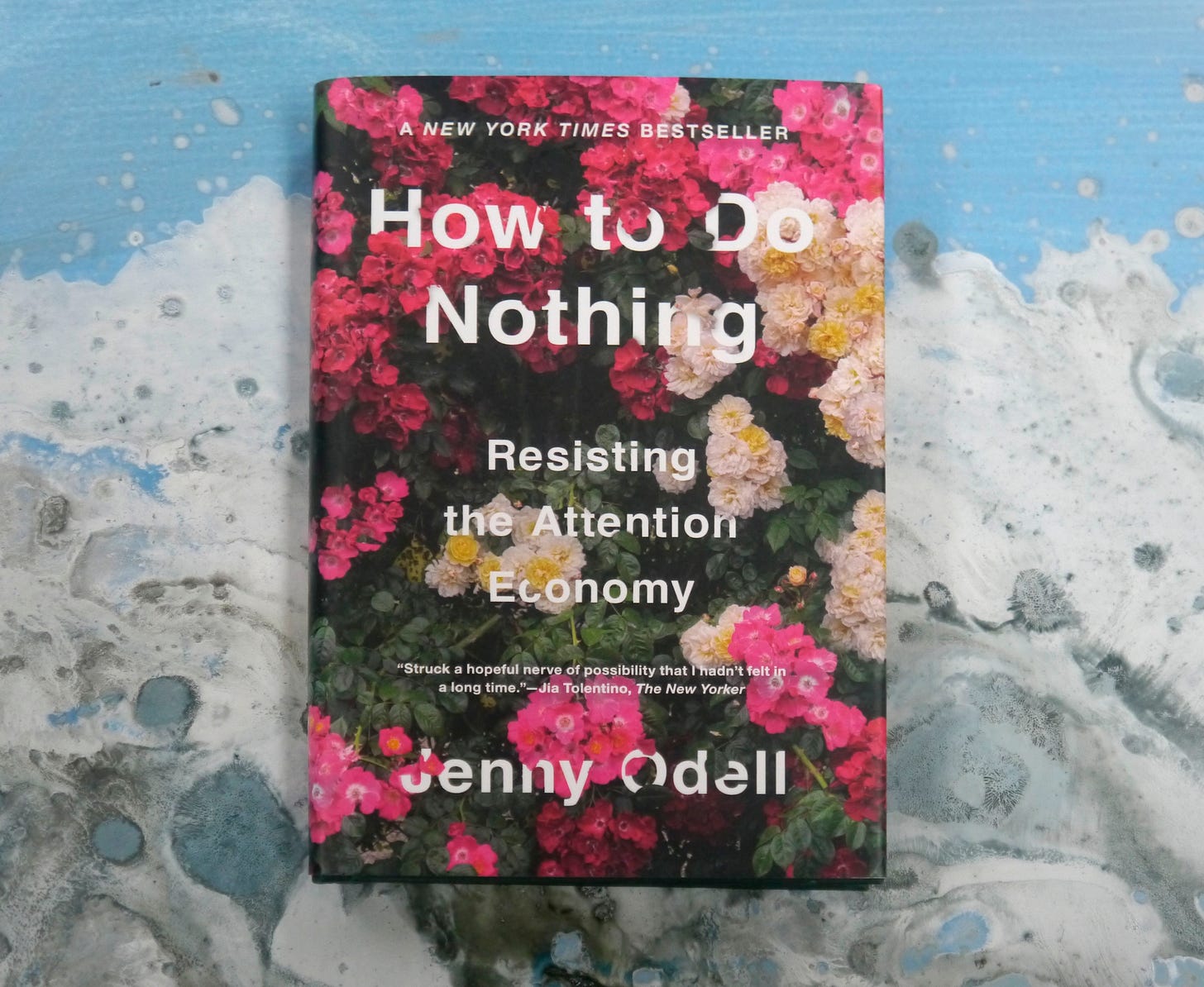

I’ve written about Jenny Odell’s wonderful book “How to do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy” before, but it’s worth mentioning again here. She writes

In my capacity as an artist I have always thought about attention, but it’s only now that I fully understand where a life of sustained attention leads. In short, it leads to awareness, not only of how lucky I am to be alive, but to ongoing patterns of cultural and ecological devastation around me – and the inescapable part that I play in it, should I choose to recognise it or not. In other words, simple awareness is the seed of responsibility.

When we pause from our reading, perhaps to gaze out of the window, to make some notes in the margin, or simply to savour the atmosphere the writing has created in us, this is when we begin to leave the author’s wisdom behind and allow some space for our own wisdom to grow. But this depth of engagement is hard won in these times.

Odell describes a feeling I certainly recognise:

By spending too much time on social media and chained to the news cycle, you are marinating yourself in the conventional wisdom, in other peoples’ reality: for others not yourself. You are creating a cacophony in which it is impossible to hear your own voice, whether it’s yourself you’re thinking about or anything else.

Odell doesn’t advocate complete rejection or retreat. You don’t need to delete all your social media accounts. It wouldn’t work anyway. There is no escaping the political fabric enmeshes us and in any case the world needs our participation, now more than ever.

But, Odell says,

We need to be able to do both: contemplate and participate, to leave and always come back, where we are needed.

How do we learn to be more conscious about where we place our attention? For Odell, taking up birdwatching has taught her both attention and patience. Animals are good teachers, she suggests.

They don’t see progress, they just see recurrence, day after day, week after week. And through them, I am able to inhabit that perspective too.

Paying attention to birds has taught her how to inhabit time differently.

For many of us, the pandemic lockdowns were an invitation to pay deeper attention to the prosaic, the everyday, the slow and repetitive things we usually overlook.

notes how walking her dog reminded her of this.The pandemic taught me to look for dear life. I know the moves but the urgency is gone. When it comes to mental focus on a walk, I could learn a thing or two from my foraging dog. Not a crumb of stale pizza gets past him.

Artist

notices how tasking herself to do nothing, a decision forced upon her by a period of ill health, has been the hardest thing she’s done this week. She notices how her brain, used to the regular dopamine hit of small, daily achievements, has had to recalibrate.To Do Nothing increases your sensitivity to dopamine. Most of our day is spent seeking out dopamine, the motivational drug our brains serve up. All that scrolling jacks your dopamine, giving you constant hits. But even when we are not on our phones, we will seek out dopamine hits from completing defined tasks. I was getting a dopamine hit from the satisfaction of completing my tax return. From clearing out my inbox.

It’s this ability to resist the craving for ‘achievement’ and finishing things that I’ll certainly be trying to cultivate over the next weeks and months. I’m at the very early stages of a big painting that will take me a long time to complete. For now, I’m just laying some background colours down. These will eventually be almost hidden beneath many much more detailed layers. I’m feeling a bit daunted by the task I’ve set myself, but I’m feeling my way into it.

No doubt you’ll see more of this piece as it develops. I suspect it may take me longer to finish than it took me to read Wolf Hall, but hopefully not longer than it took Hilary Mantel to write it!

Life Raft Co-Working Zoom

Join us for our weekly co-working session, every Wednesday 3pm - 4pm on Zoom. Such a lovely warm and supportive group is emerging here, with many regulars showing up every week. Here’s the link:

And if you weren’t able to join us last week or fancy checking us out before you join us live, you can view last week’s recording here. Passcode 3nt%Z!4.

As always, thank you for reading, and I hope you find something of value here. If you’ve been a regular reader of this newsletter for a while, and think it’s worth the price of a fancy latte, do consider upgrading to a paid subscription. Those of you who have, you know who you are, and I thank you wholeheartedly. I put a lot of love into writing this every week, and your subscription tells me my efforts are appreciated.

Until next week!

Sam

P.S. If you enjoyed this post you might like this one too….

Art that holds time as a vase holds water

Last week I ventured forth from my quiet island home in Orkney and made a rare expedition to the Bright Lights of the Big City, to spend a few days in London. Mostly we were visiting old friends, but I also took the chance to recharge my art batteries by seeing some exhibitions.

Well said Samantha, I couldn’t agree more. I’ve just completed a painting I started 7 years ago, for me it’s always the same, the journey not the getting there (though we need that as well!) the slow hypnotic contemplation/meditation and the quiet, receptive tuning into what is revealed. I see this as a form of prayer - what is not known is always more enriching than the known.

Everything you’ve said here Samantha. I made the choice of War and Peace with Simon this year and I haven’t regretted it. It’s a wonderful way to read, slow and in community. But I’m hoping Simon continues next year again with Wolf Hall - I just knew I wouldn’t manage both together.

Looking forward to getting on to your lovely life raft later this afternoon. It’s a balm.